Cryphalus asperatus

| Notice: | This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly. This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX: @article{Justesen2023ZooKeys1179, RIS/ Endnote: TY - JOUR Wikipedia/ Citizendium: <ref name="Justesen2023ZooKeys1179">{{Citation See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Ordo: Coleoptera

Familia: Curculionidae

Genus: Cryphalus

Name

Cryphalus asperatus (Gyllenhal, 1813) – Wikispecies link – Pensoft Profile

- Bostrichus asperatus (Gyllenhal, 1813: 368); designated by Wood 1972[1]: 41.

- Bostrichus abietis (Ratzeburg, 1837: 161) (syn: Wood 1972[1]).

Type material

Destroyed during the Second World War together with C. piceae type material (see C. piceae).

Neotype designation

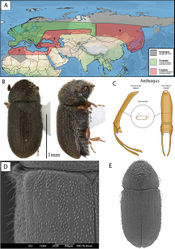

We designate a neotype of Cryphalus asperatus with the express purpose of clarifying the taxonomic status. In the original description, the distribution of C. asperatus is mentioned from Upper Silesia (Poland), East Prussia (Poland/Russia), Thuringian Forest (Germany) and Harzen (Germany) and the species is mentioned from Picea Mill. (Ratzeburg, 1837). A neotype of Cryphalus asperatus (Gyllenhal, 1813) is designated (Fig. 15). It is a male collected on 18/05-2023 from a Picea abies branch collected in Czechia (Silensia) (48°58'20.9"N, 19°35'16.2"E) not far from Upper Silesia. The specimen will be stored at NHMD in the entomological collections.

Material examined

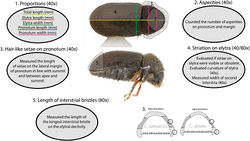

599 specimens from 8 countries in Europe (Table 1) were examined. Morphological measurements were done on 38 specimens from Romania (7), Czechia (12), Slovakia (6), Netherlands (6), and Belgium (7). The results are presented in Fig. 2.

Diagnosis

This species can be diagnosed from similar Cryphalus in Europe by the combination of body size usually < 1.75 mm (average 1.61 mm), setae on lateral margin of pronotum clearly shorter between apex and summit compared to setae in line with summit (character 3, Fig. 1), randomly distributed asperities on pronotal declivity (< 50), interstrial setae on the elytral declivity shorter than width of second interstria, often clear elytral striation. For confident identification, extraction of male genitalia is recommended. Penis body when seen dorsally is, aside from the apex, equally broad and is almost bilateral in symmetry. The entire aedeagus ~ 0.5 mm in length (Fig. 16B–E).

Description

Length 1.38–1.90 mm, average 1.61 mm. Proportions: 2.3× as long as wide, elytra 1.5× as long as wide, elytra 1.95× longer than pronotum. Antennae: club with three procurved sutures marked by long setae. Funiculus with four antennomeres (including pedicel). Pronotum: dark brown to black on both slope and disc. Profile anterior to summit triangular to rounded, slightly wider in line with summit. Anterior margin with 2–7 asperities, the outer pair usually smaller, and with erect setae in line with the summit and near apex, usually short or upwards facing in-between. Anterior slope with < 50 asperities, including the ones on the anterior margin. Disc between 1/4–1/5 the length of entire pronotum, gently sloped, weakly tuberculate surface texture with a small hair-like setae in each tubercule. Vestiture on declivity and disc hair-like. Suture between pronotum and elytra weakly sinuate. Scutellum: completely covered with trifurcate hair-like setae (Fig. 16D). Elytra: usually black or dark brown but occasionally light brown, margins parallel and straight. The curvature on the declivity regularly rounded. Surface smooth. Striae often visible as rows of punctures with a short hair-like seta arising from each puncture. Interstrial setae short (0.05–0.08 mm) and erect. Interstrial ground vestiture is serrated, ~ 2–3× as long as wide and translucent brown with a weak iridescence (Fig. 16B, D, E). Proventriculus: sutural teeth of irregular size, confused, in two or more longitudinal rows. Apical teeth extend laterally to < 2/3 of the plate. Masticatory brush slightly < 1/2 of the proventricular length (Fig. 7).

Sexual dimorphism. Males and females can be separated using the last ventrite (Fig. 11), as suggested by (Johnson et al. 2020a[2]). Wood (1982)[3] also suggests that the sexes of several scolytines including Cryphalus, can be separated by males having a clearly visible 8th tergite and the females a highly reduced or absent 8th tergite. This character was not examined. No obvious differences in tubercles or carina on the frons was noticed.

Male. The aedeagus is ~ 0.5 mm long when measured vertically (i.e., from the two points furthest away from each other). The penis body when seen from above is at the side of the apex, equally broad, and almost bilaterally symmetrical and < 0.4 mm. Aedeagus apodemes makes up ~ 35% of the entire aedeagus length when measured vertically and are more or less straight and bending downwards. The tegmen is sclerotised and completes a ring around the penis body. It is thin and has two ventral apodemes, which are ~ 1/2 the length of the distance between them. The dorsal part of the tegmen ring is narrowest in the middle (Figs 5, 16C).

Larvae. For a description of larvae see the work by Ritchie (1918)[4] or Lekander (1968)[5].

Host plants

This species is mentioned in the literature from several conifer genera, but primarily from different Picea species (Escherich 1923[6]; Hansen 1956[7]; Lekander et al. 1977[8]; Grüne 1979[9]; Wood 1992b[10]). In a study designed to test the specificity of bark beetles to different conifer hosts, C. asperatus was found to prefer Abies and Picea over Pinus and Cupressus (Chararas et al. 1982[11]). Ritchie (1918)[4] found Abies as a preferred host plant of C. asperatus. We collected C. asperatus in large numbers from monocultural Abies procera Rehder plantations in Denmark, which seem to support these data (Justesen et al. 2017[12]; pers. obs. MJJ).

Distribution

According to the Palearctic catalogue (Knížek 2011[13]; Alonso-Zarazaga et al. 2023[14]), C. asperatus is found in Europe: Austria, Belgium, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Belarus, Czechia, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Great Britain, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Macedonia, Montenegro, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Russia: Central European Territory, North European Territory, South European Territory; North Africa: Algeria, Morocco; Asia: Japan, North Korea, Turkey, Russia: East Siberia, Far East.

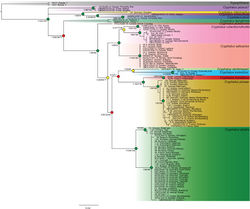

The catalogue reported C. asperatus in all European countries except Portugal, Ukraine, Moldova, Albania, and Serbia. Nikulina et al. (2015)[15] collected C. asperatus in Ukraine and Marković (2013)[16] in Serbia. Considering the natural distribution of Picea and Abies in Albania, it is unlikely that C. asperatus is not present here as well. Studies from Finland (Voolma et al. 2004[17]) and distribution maps from Sweden (Artportalen 2023[18]) and Norway (Artsdatabanken 2023[19]), show that C. asperatus is not adapted to the Arctic region. The fact that the catalogue mentions C. asperatus from Japan, North Korea, and Eastern Russia needs confirmation. Distribution records from these areas could be erroneous because of similar looking species, e.g., Cryphalus sichotensis Kurenzov, 1941, C. saltuarius or others. More comparative work on the eastern species, similar to that of Johnson et al. (2020b)[20], is necessary to figure out the easternmost extent of C. asperatus. Our distribution map follows the note by Mandelshtam (2002)[21] stating that C. asperatus is not found east of Altai (Mandelshtam 2002[21]). Records of C. asperatus in Morocco and Algeria also need confirmation, especially considering the one specimen (1.28: Georgia, Tlughi) from Georgia, which is 5.6% different from the European populations (Fig. 8). A larger sampling in and around Georgia, including in-depth morphological study are needed to elucidate the relationship and establish if these specimens represent a separate species or just intraspecific variation. See distribution illustrated in Fig. 16A.

Bionomics

During winter C. asperatus can hibernate as adults, larvae, pupae and more rarely as eggs (Ritchie 1918[4]; Pfeffer 1955[22]). It hibernates underneath the bark of infested material (Ritchie 1918[4]; pers. obs. MJJ). Flight activity can start already in March (Ritchie 1918[4]; data from Wermelinger et al. (2002)[23]; pers. obs. MJJ). Comparable unpublished data from Denmark showed that C. asperatus became active a few weeks earlier than C. piceae. During the period from March to May C. asperatus aggregates on suitable material and mates. The males will try to mate with as many females as possible, and after mating the males will excavate a nuptial chamber. Males of C. asperatus display a very distinct preference for branch nodes, and often you find branches where only nodes are inhabited (Ritchie 1918[4]; Justesen et al. 2017[12]). This preference is so evident that it was mentioned in the original description by Ratzeburg (1837)[24]. The preferred material seems to be moist and shaded branches, compared to sun exposed dry branches (Ritchie 1918[4]; pers. obs. MJJ). Compared to the other European Cryphalus species, C. asperatus can target relatively old/decomposed material but can also be found in recently fallen branches. Once the males complete their nuptial chamber, the female will lay 14–24 eggs (Ritchie 1918[4]). The development from egg to adult is variable depending on temperature, type of material, the position of the material (sun-exposed) and the time of egg-laying (Ritchie 1918[4]). According to Ritchie (1918)[4] two generations per year is unlikely, but he mentions the possibility of a sister generation. Grüne (1979)[9] and Pfeffer (1955)[22] suggested two generations per year. In an unpublished study from Denmark, 90 Abies procera branches were cut and placed as bait in an A. procera plantation in the spring. Six branches were then collected every second week and evaluated for the presence of various life stages of C. asperatus. These results suggested one generation. Based on the above information, C. asperatus most likely has two generations under ideal conditions and only one in colder climates.

Economic significance

In older literature C. asperatus is described as a possible harmful pest (Eichhoff 1881[25]; Nüßlin 1905[26]; Bodenheimer 1958[27]). However, as already mentioned by Ritchie (1918)[4] and Hansen (1956)[7], these reports seem unlikely. A recent study looking at Norway spruce seedlings weakened by transport, found C. asperatus as a potential problem (Fiala and Holuša 2021[28]). Our observations of C. asperatus support that this species is a harmless species not able to kill or weaken trees.

Remarks

Differences between C. asperatus and C. saltuarius.

The shape and size of the aedeagus is the best character to separate the two species. The penis body when seen dorsally is equally broad in C. asperatus, but broadest one quarter down from the apex and then becomes increasingly narrow towards the base in C. saltuarius. The entire aedeagus is longer (~ 0.7 mm) in C. saltuarius compared to C. asperatus (~ 0.5 mm).The size difference between C. asperatus and C. saltuarius is commonly highlighted and the following lengths were reported for C. asperatus: 1.75 mm average (Ritchie 1918[4]), 1.2–1.7 mm (Grüne 1979[9]; Pfeffer 1995[29]; Noblecourt and Schott 2004[30]), 1.2–1.8 mm (Hansen 1956[7]), and 1.3–1.8 mm (Spessivtseff 1922[31]). We measured 38 C. asperatus specimens and found a range of 1.38–1.90 mm but, besides one noticeably larger specimen, the remaining 37 specimens were all < 1.75 mm. The following lengths were reported for C. saltuarius: 1.5–2 mm (Spessivtseff 1922[31]; Hansen 1956[7]; Grüne 1979[9]; Pfeffer 1995[29]) and 1.5–2.2 mm (Noblecourt and Schott 2004[30]). We measured 25 specimens of C. saltuarius to 1.73–1.98 mm, with eight specimens lying between 1.73–1.75 mm. These measurements confirm that body size often is a reliable character, but also highlights that overlap occurs.

We found that C. saltuarius specimens usually had longer and perpendicularly erect setae along the margins of pronotum (Figs 1, 17B, E), whereas most C. asperatus only had erect setae in line with the summit and near apex, and then short and sometimes upwards facing setae in-between apex and summit (Fig. 16B, E). It should be mentioned that authors have observed old C. saltuarius museum specimens lacking these setae. The scutellum of C. asperatus is covered in trifurcate hair-like setae, whereas C. saltuarius only has these hairs along the elytral margin of scutellum (Figs 16D, 17D); however, this character requires high magnification and was therefore not included in the key. Several keys mention that the striae in C. asperatus are clearer (Fig. 16B, D, E) compared to more indistinct striae in C. saltuarius (Fig. 17B, D, E) (Ritchie 1918[4]; Spessivtseff 1922[31]; Hansen 1956[7]; Grüne 1979[9]; Pfeffer 1995[29]; Noblecourt and Schott 2004[30]). Generally, we could confirm this tendency (Fig. 4), but nine of the 25 C. saltuarius specimens had clearer striation, which could be confused with C. asperatus specimens with less distinct striation.

Noblecourt and Schott (2004)[30] used the shape of the elytral declivity to separate C. asperatus (regular curvature) from C. saltuarius (flattened on the declivity). Our studies also found this tendency, but with a slight overlap (Fig. 4).

Most keys include proportional differences as a good character to separate the species. Noblecourt and Schott (2004)[30] found C. asperatus was 2.3× longer than wide and C. saltuarius 2× longer than wide. Our results (Fig. 2) showed a slight tendency of C. asperatus being comparably longer than wide, but with a very high degree of overlap between the species. Grüne (1979)[9] and Pfeffer (1995)[29] found that the elytra of C. asperatus was 1.5–1.57× as long as wide, whereas C. saltuarius was 1.6–1.67× as long as wide. Our measurements had a large overlap in the proportional difference of elytra. Therefore, we did not find proportions as a good character. It should be noted that we measured elytral width as in Fig. 1, across the scutellum. Measurements 1/3 down from the basal border of elytra could slightly increase the width measurements, resulting in less similar proportions.

Taxon Treatment

- Justesen, M; Hansen, A; Knížek, M; Lindelow, Å; Solodovnikov, A; Ravn, H; 2023: Taxonomic reappraisal of the European fauna of the bark beetle genus Cryphalus (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Scolytinae) ZooKeys, 1179: 63-105. doi

Images

|

Other References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wood S (1972) New synonymy in the bark beetle tribe Cryphalini (Coleoptera: Scolytidae).The Great Basin Naturalist32(1): 40–54. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41711335 [Accessed 03 February 2023]

- ↑ Johnson A, Hulcr J, Knížek M, Atkinson T, Mandelshtam M, Smith S, Cognato A, Park S, Li Y, Jordal B (2020a) Revision of the bark beetle genera within the former Cryphalini (Curculionidae: Scolytinae).Insect Systematics and Diversity4(3): 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1093/isd/ixaa002

- ↑ Wood S (1982) The bark and ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a taxonomic monograph.Memoirs of the Great Basin Naturalist6: 1–1359. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/248626 [Accessed 03 February 2023]

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Ritchie W (1918) The structure, bionomics and forest importance of Cryphalus abietis Ratz.Annals of Applied Biology5(3–4): 171–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1919.tb05289.x

- ↑ Lekander B (1968) Scandinavian bark beetle larvae: descriptions and classification. Rapport Uppsats.Institutionen for Skogszoologi, Stockholm, Skogshogaskolan, 186 pp.

- ↑ Escherich K (1923) Die Forstinsekten Mitteleuropas (Vol. 2). Parey, Berlin, 342–380.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Hansen V (1956) Barkbiller.Danmarks fauna, Gads forlag, København, 196 pp. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/36123520 [Accessed 03 February 2023]

- ↑ Lekander B, Bejer-Petersen B, Kangas E, Bakke A (1977) The distribution of bark beetles in the Nordic Countries.Acta Entomologica Fennica32: 1–37. [78 maps]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Grüne S (1979) Brief Illustrated Key to European Bark Beetles. Verlag M. & H.Schaper, Hannover, German Federal Republic, 182 pp.

- ↑ Wood S (1992b) A Catalog of Scolytidae and Platypodidae (Coleoptera), Part 2: Taxonomic Index. Volume B. Great Basin naturalist memoirs 13: 1553. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8897072 [Accessed 03-02-2023]

- ↑ Chararas C, Revolon C, Feinberg M, Ducauze C (1982) Preference of certain Scolytidae for different conifers.Journal of Chemical Ecology8(8): 1093–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00986980

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Justesen M, Hansen A, Thomsen I, Ravn H (2017) Nye og gamle trusler mod nobilis.Nåledrys99: 36–40.

- ↑ Knížek M (2011) Scolytinae. In: Löbl I Smetana A (Eds) Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera (Vol.7), Curculionoidea I. Apollo Books, Steenstrup, 86–87. [204–251]

- ↑ Alonso-Zarazaga M, Barrios H, Borovec R, Bouchard P, Caldara R, Colonnelli E, Gültekin L, Hlaváč P, Korotyaev B, Lyal C, Machado A, Meregalli M, Pierotti H, Ren L, Sánchez-Ruiz M, Sforzi A, Silfverberg H, Skuhrovec J, Trýzna M, Velázquez de Castro A, Yunakov N (2023) Cooperative catalogue of Palaearctic ColeopteraCurculionoidea. Monografias Electrónicas, Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa 14: e780.

- ↑ Nikulina T, Mandelshtam M, Petrov A, Nazarenko V, Yunakov N (2015) A survey of the weevils of Ukraine. Bark and ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae and Scolytinae).Zootaxa3912(1): 1–61. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3912.1.1

- ↑ Marković Č (2013) Collection of bark beetles (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) formed by Professor dr. Svetislav Živojinović. Acta Entomologica Serbica 18(1/2): 137–160.

- ↑ Voolma K, Mandelshtam M, Shcherbakov A, Yakovlev E, Õunap H, Süda I, Popovichev B, Sharapa T, Galasjeva T, Khairetdinov R, Lipatkin V, Mozolevskaya E (2004) Distribution and spread of bark beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) around the Gulf of Finland: a comparative study with notes on rare species of Estonia, Finland and North-Western Russia.Entomologica Fennica15(4): 198–210. https://doi.org/10.33338/ef.84222

- ↑ Artportalen (2023) Cryphalus asperatus. Map search. https://artfakta.se/artinformation/taxa/cryphalus-asperatus-106587/detaljer

- ↑ Artsdatabanken (2023) Cryphalus asperatus. Map search. https://artsdatabanken.no/Pages/264269/Kart [Accessed 11 March 2023]

- ↑ Johnson A, Li Y, Mandelshtam M, Park S, Lin C, Gao L, Hulcr J (2020b) East Asian Cryphalus Erichson (Curculionidae, Scolytinae): New species, new synonymy and redescriptions of species.ZooKeys995: 15–66. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.995.55981

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mandelshtam M (2002) New synonymy, new records and lectotype designation in Palaearctic Scolytidae (Coleoptera).Far Eastern Entomologist119: 6–11. https://www.zin.ru/journals/zsr/content/2000/zr_2000_9_1_Mandelshtam.pdf [Accessed 03 February 2023]

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Pfeffer A (1955) Kůrovci – Scolytoidea. Fauna ČSR, svazek 6.ČSAV, Praha, 324 pp. [+ 42 Tab.]

- ↑ Wermelinger B, Duelli P, Obrist M (2002) Dynamics of saproxylic beetles (Coleoptera) in windthrow areas in alpine spruce forests. Forest Snow and Landscape Research 77(1/2): 133–148.

- ↑ Ratzeburg J (1837) Die Forst-Insecten oder Abbildung und Beschreibung der in den Wäldern Preussens und der Nachbarstaaten als schädlich oder nützlich bekannt gewordenen Insecten. Die Käfer Erster Theil. Nicolai, Berlin, [x + 4 +] 202 pp [21 pls].

- ↑ Eichhoff W (1881) Die Europäischen Borkenkäfer: für Forstleute, Baumzüchter und Entomologen. J. Springer, Berlin, [viii +] 315 pp. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.8968

- ↑ Nüßlin D (1905) Leitfaden der Forstinsektenkunde. Berlin, Verlagsbuchhandlung Paul Parey, SW. Hedemannstrasse 10: e1905. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.16428

- ↑ Bodenheimer F (1958) Türkiye’de Ziraate ve Ağaçlara Zararlı Olan Böcekler ve Bunlarla Savaş Hakkında bir Etüt.Bayur Matbaası, Ankara, 346 pp.

- ↑ Fiala T, Holuša J (2021) Infestation of Norway spruce seedlings by Cryphalus asperatus: New threat for planting of forests? Plant Protection Science 57(2): 167–170. https://doi.org/10.17221/112/2020-PPS

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Pfeffer A (1995) Zentral- und Westpaläarktische Borken- und Kernkäfer (Coleoptera: Scolytidae, Platypodidae).Pro Entomologia, Basel, 310 pp.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Noblecourt T, Schott C (2004) Cryphalus intermedius Ferrari, 1867 et Cryphalus saltuarius Weise, 1891, espèces nouvelles pour la faune de France.Bulletin Mensuel de la Societe Linneenne de Lyon73(7): 290–292. https://doi.org/10.3406/linly.2004.13532

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Spessivtseff P (1922) Bestämningstabell över svenska barkborrar (Häfte 19: 6).Meddelande från statens skogsförsöksanstalt19: 453–492.