Rhytidognathus platensis

| Notice: | This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly. This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX: @article{Roig-Juñent2012ZooKeys247, RIS/ Endnote: TY - JOUR Wikipedia/ Citizendium: <ref name="Roig-Juñent2012ZooKeys247">{{Citation See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Ordo: Coleoptera

Familia: Carabidae

Genus: Rhytidognathus

Name

Rhytidognathus platensis Roig-Juñent & Rouaux, 2012 sp. n. – Wikispecies link – ZooBank link – Pensoft Profile

Type material

Holotype: male, Argentina: Buenos Aires, Los Olmos (MLP); Paratypes, same date, one male two females (MELP, IADIZA); Entre Ríos(MACN), one female.

Diagnosis

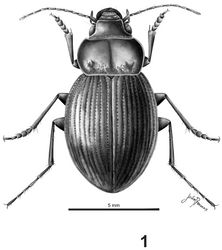

Head with small punctures, on the borders; elytra black with interstria 8 reddish; labrum with the borders yellowish; interstriae flat; apex of median lobe sub-quadrangular.

Description

Habitus as in Fig. 1. Length: 10.3 mm. Coloration: black; with antennae light colored, reddish, and legs testaceous, dark reddish. Labrum with borders yellowish; elytra black with interstria 8 reddish.

Head. Head with small punctures in front; eyes slightly protruding, rounded (Fig. 8). Maxillary palpi black or dark red.

Prothorax. Wider than long, maximum width at middle (Fig. 5); dorsal surface with punctures on the base (Figs 1, 5), apex with small or no punctures. Lateral margins narrow, curved; central longitudinal sulcus slightly developed; posterior transverse foveae slightly impressed. Posterior angles rounded. Prosternum without punctures or one or two on the apex. Prosternal projections not marginate, with a small apical tubercle, sinuate dorsally (Figs 6, 9).

Metathorax.Elytra with humeral angles rounded (Fig. 7); striae on basal third well impressed, and foveate, less impressed at apex. Ninth interval with six setae; elytral interval flat.

Male genitalia(Figs 14–17). Median lobe wide, with apex sub-quadrangular (Figs 14-16), apical orifice big, open dorsally and straight; basal orifice wide, closed dorsally (Fig. 14), without basal keel. Left paramere wide with apex rounded (Fig. 16), setae on apical third (Fig. 16). Right paramere thin, constricted in the middle, with setae from middle to apex (Fig. 16).

Female genital track(Fig. 18). With gonopod VIII small. Gonopod IX dimerous, the base with two sclerites, the apex small without setae, with apical setose organ (Fig. 18). Bursa copulatrix large, without accessory glands. Spermatheca on the base of oviduct, digitiform. Bursa copulatrix with a large sclerite.

Etymology

The name of the new species is related to the area where it was collected, La Plata district, near the La Plata river in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina.

Taxonomic considerations

Tremoleras (1931)[1] cited Rhytidognathus ovalis for Argentina. Tremoleras` specimen was held in his collection and now we can not find it. The description by Tremoleras (1931)[1] does not allow a clear identification of this material. Roig-Juñent (2004)[2] cited also Rhytidognathus ovalis for Entre Ríos province (Argentina), based on a female. In the presentcontribution, this female specimen is now considered as being Rhythidognathus platensis. Taking into account that Rhythidognathus platensis is distributed along the western shore of the La Plata river, we considered it more likely that Tremoleras` specimen belongs to the new species, Rhythidognathus platensis, and not to Rhythidognathus ovalis.

Distribution

Argentina: Buenos Aires: San Isidro(Tremoleras 1931[1]); Los Olmos (La Plata); Entre Ríos.

Habitat

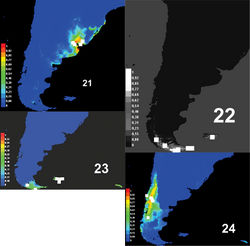

The new material was collected in the locality of Lisandro Olmos (La Plata, Buenos Aires) at “La Nueva Era” farm (35°01'18"S, 58°02'07"W) (Fig. 20), devoted to horticultural production under organic management (Fig. 21). The area has elevations of about 30 m, with soils derived from the Buenos Aires belt corresponding to grassland soils. It is surrounded by horticultural crops grown under cover and in the open, primarily tomato, pepper, leafy vegetables, celery, eggplant and small plots of corn, among others. Cut flower production in greenhouse conditions is also important in this area.

Samples were collected by pitfall traps set up in a 2000 m2-area cultivated with lettuce (Lactuca sativa), onion (Allium cepa), radish (Raphanus sativus), rocket (Diplotaxis sp.), cabbage (Brassica oleracea) and different types of weeds. This habitat has no native vegetation. Probably Rhytidognathus platensis inhabits the patches of semi-natural vegetation surrounding the crops. It has been proven that carabids move between cultivated and uncultivated patches (Marshall and Moonen 2002[3], Magura 2002[4]).

On the shores of La Plata river in Buenos Aires province we found two natural habitats. One habitat is close to the river and includes: a) cliffs, with small forest of Celtis tala and other arboreal species, b) riparian shallows extending between the cliffs and the river and constituting a low plain that gets flooded, similar to the marshes of the Paraná river delta. The soil is clay and salty, and the vegetation is characterized by halophytic steppe with dominance of low grasses such as Distichlis spicata. The second habitat, the Pampean plain, lies above the cliffs. This lowland has a temperate climate, with an even year-round precipitation regime, soil type is loam, and the plants that dominate the landscape are herbs that compose the extensive Pampean grassland, a steppe. The typical original plant community comprises species of the genera Stipa and Piptochaetium. This landscape is accompanied on different sites by low shrubs of several species of Bacharis.

Predictive models of distribution show that the genus Rhytidontahus isrestricted to the coast and areas close to the La Plata river and the delta of the Paraná and Uruguay Rivers (Fig. 20), occupying shore habitats and the Pampean grassland near the shore. This Pampean plain has been strongly modified, allowing for great agricultural development with establishment of annual crops and pastures, leaving hardly any native vegetation in the region. The Pampean grassland and forest close to the La Plata river and to the high Paraná River differ in species and habitat conditions from the areas inhabited by nearly all sister groups of Rhytidognathus, the genera Lissopterus Waterhouse, Migadopidius Jeannel and Pseudomigadops. Migadopidius occupy temperate Nothofagus forests(Fig. 24, Table 1). Lissopterus and Pseudomigadops (Figs 22-23) occur in habitats closer to the shore, principally sub-Antarctic forest or moorlands (Figs 22–23, Table 1). The unique genus of the sister group inhabiting grassland is Pseudomigadops, in some part of Malvinas Islands. As we can see, Pseudomigadops inhabits coastal forest and grassland, like Rhytidognathus, but species composition in their habitats is far from being the same, as the former is of sub-Antarctic origin and the other of Neotropical origin (Morrone 2004[5]). Climatic conditions are not the same either, and if we look at the variables that explain the predictive models of distribution of these four Migadopini genera, the most important variable is temperature (Table 1).

Biogeographic considerations Because of its particular distribution pattern and its phylogenetic relationships with other tribes, the Migadopini have been used to explain some very different biogeographic views, such as an austral origin and separation by vicariance (Jeannel 1938[6], Brundin 1966[7]) or a Holarctic origin, separate dispersal to the southern continents, extinction in tropical and subtropical regions (Darlington 1965[8]). Beyond the different proposals regarding the origin of the tribe, everybody considers that its current restricted distribution is relictual (Jeannel 1938[6], Darlington 1965[8]). Upon the advent of the theory of plates as applied to the continental drift, it was put forward that many groups with distribution patterns similar to those of migadopines be considered of austral origin, whose fragmentation led to their present distribution. By applying a Dispersal and Vicariance analysis, Roig-Juñent (2004)[2] put both hypotheses to test and his conclusions concur with Jeannel’s saying that the tribe has had an origin in the southern hemisphere and that its current distribution across the southern continents has been due to vicariant events. Notwithstanding, the analysis yielded no support for the existence of three separate phyletic lines (monophyletic groups): Australian, New Zealander and American, as Jeannel proposed (1938[6]). This shows that some clades would have originated before the fragmentation of some parts of Gondwana.

Regarding the present distribution of the Migadopini in South America, it is restricted to three disjunct areas. The first is in the Ecuadorian Andes, where the genus Aquilex occurs at about 4300 m elevation at Páramo (Moret 1989[9]); the second is on the shores of the La Plata river where Rhytidognathus lives in Pampean grassland and riparian forest environments; and the third, which is the largest in surface area and coincides with the sub-Antarctic region in Chile and Argentina, includes all Nothofagus forests and sub-Antarctic regions up to Cape Horn. The latter is the area with highest number of Migadopini genera, and where most taxa show more phylogenetic affinity to other taxa from southern regions (New Zealand, Australia) than to those from the rest of the Neotropics. Although the present distribution of the Migadopini is largely restricted to the sub-Antarctic region in South America, it is likely that, at some point of the Cenozoic, the tribe may have had a broader distribution. The sub-Antarctic biota expanded to more northern areas and its later retraction left areas with relictual distributions. Such is the case of the Fray Jorge forests in Chile (30° 40´44” S, 71° 40´54” W) or the Araucaria forests in the south of Brazil and north of Argentina (26° 27¨S, 53° 37´W). This expansion might explain the presence of Rhytidognathus in the La Plata river because, being apterous and large-sized, this taxon has almost no capacity for dispersal. Moret (1989)[9] considers the same situation for the genus Aquilex, which would have originated from its southern ancestors in the pulses of northward expansion of the sub-Antarctic biota during the Cenozoic.

Considering the particular distribution of Rhytidognathus, the biogeographic analysis carried out by Roig-Juñent (2004)[2] shows that this genus would have been split by a vicariant event from its sister group (Lissopterus + Pseudomigadops + Migadopidius) which now inhabits the Magellanic region or the northern Nothofagus forests. Although the distance to the Magellanic region exceeds 3000 km and is 1000 kmto the Nothofagus forest region, the possibility of a vicariant event is feasible because, as mentioned for the austral region of South America, its cold austral biota experienced expansions during the Cenozoic whereby the genus came to occupy areas more northern than the current ones (Romero 1986[10], Barrera and Palazzesi 2007). So the separation of Rhytidognathus may have been caused either by vicariance or by isolation upon the southward retraction of the austral biota. Numerous are the relictual taxa than can be found in the Pampean region and south of Brazil, such is the case among carabids of the tribe Broscini.

In analyzing the environmental features of each genus, we find that there could also have been environmental features involved in the split. Figures 21–24 show the potential distribution range of Rhytidognathus and that of its sister genera. For these four genera, we find three clearly separate areas, one is austral sub-Antarctic, another one comprises the cold-temperate forests, and the third one encompasses the Pampean steppe and riparian forests along the La Plata river. The Pampean region is the exception with respect to the other habitats where migadopines occur in South America, and to the remaining circum-Antarctic regions, because most are from cold-temperate or cold environments, such as the species of Loxomerus Chaudoir (Johnson 2010). Although the Pampean grassland is a temperate area, it has warm summers and the vegetation is Neotropical in origin, not austral.

In other cases, it has been put forward that there often is niche conservation, commonly observed in species of the same genus whose potential distributions show areas occupied by other species of the genus rather than by them. However, we see that a shift has occurred among these four genera regarding the environment occupied by some of them. We propose that the environment occupied by the ancestor of Rhytidognathus and the sister group could have been cold-temperate coastal or riparian habitats, either forest or grassland (present in Rhytidognathus and Pseudomigadops). An arid barrier formed during the Cenozoic between the Pampean and sub-Antarctic regions (Barreda and Palazzesi 2007[11]), isolating Rhytidognathus, and the current species of this genuswould have had to become adapted to this more temperate climate.

| Habitat | variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Rhytidognathus | Lowlands, 30-m altitude, in Pampean grasslands, and probably in riparian forests along the La Plata river and the Paraná river delta. | 67.3%: Isothermality:17.0% :Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation)10.1 Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter |

| Pseudomigadops | Lowlands, sea level to 10-meter altitude; in Malvinas grasslands (mainly of Poa flabellata) and Magellanic moorland (of Empetrum rubrum).In Navarino, southern Tierra del Fuego (near Beagle Channel), Isla de los Estados and Cape Horn Nothofagus betuloides forest on the coast and Magellanic moorland (Empetrum rubrum) (Niemela 1990) | 46.9% Max Temperature of Warmest Month14.7 % Mean Temperature of Driest Quarter11.8 % Mean Annual Temperature |

| Lissopterus | Lowlands, sea level to 5-meter altitude; in Malvinas grasslands (mainly of Poa flabellata) and Magellanic moorland (of Empetrum rubrum).In Navarino, southern Tierra del Fuego (near Beagle Channel), Isla de los Estados and Cape Horn Nothofagus betuloides forest on the coast and Magellanic moorland (Empetrum) (Niemela 1990).Sub-Antarctic maritime areas including off-shore and more remote islands (Erwin 2011) | 66.0% Max Temperature of Warmest Month11.9% Altitude6.1% Annual Temperature Range |

| Migadopidius | Nothofagus forest and Araucaria habitat; mixed forest (Araucaria araucana, Nothofagus dombeyi, Nothofagus antarctica and Nothofagus pumilio) (Dapoto et al. 2005) | 63.0% Mean Temperature of Wettest Quarter29.0% Precipitation of Coldest Quarter |

Original Description

- Roig-Juñent, S; Rouaux, J; 2012: A new species of Rhytidognathus (Carabidae, Migadopini) from Argentina ZooKeys, 247: 45-60. doi

Other References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Tremoleras J (1931) Notas sobre Carábidos Platenses. Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina 3(15): 239–242.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Roig-Juñent S (2004) Los Migadopini (Coleoptera: Carabidae) de América del Sur: Descripción de las estructuras genitales Masculinas y femeninas y consideraciones filogenéticas y biogeográfícas. Acta Entomológica Chilena 28(2): 7–29.

- ↑ Marshall E, Moonen A (2002) Field margins in northern Europe: their functions and interactions with agriculture. Ecosystems and Environments 89: 5-21. doi: 10.1016/S0167-8809(01)00315-2

- ↑ Magura T (2002) Carabids and forest edge: spatial pattern and edge effect. Forest Ecology and management 157: 23-37. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00654-X

- ↑ Morrone J (2004) Panbiogeografía, components bióticos y zonas de transición. Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 48 (2): 149-162. doi: 10.1590/S0085-56262004000200001

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jeannel R (1938) Les Migadopides (Coleoptera, Adephaga), une lignee subantarctique. Revue Française d´ Entomologie 5 (1): 1-55.

- ↑ Brundin L (1966) Transantarctic relationships and their significance, as evidenced by chironomid midges, with a monograph of the subfamilies Podonominae and Aphroteniinae and the austral Heptagyiae. Kungla Svenska Vetenskapsakad. Handlingar 11 (1): 1-471.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Darlington P (1965) Biogeography of the southern end of the world. Distribution and history of the far southern life and land with assessment of continental drift. Cambridge, Massachuset, Harvard University press, 236 pp.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Moret P (1989) ) 6 (3): 245-257.

- ↑ Romero E (1986) Paleogene Phytogeography and climatology of South America. Annual of the Missouri Botanical Garden 73: 449-461. doi: 10.2307/2399123

- ↑ Barreda V, Palazzesi L (2007) Patagonian vegetation turnovers during the Paleogene-Early Neogene: origin of Arid-Adapted Floras. The botanical review 73 (1): 31-50. doi: [31:PVTDTP2.0.CO;2 10.1663/0006-8101(2007)73[31:PVTDTP]2.0.CO;2]

Images

|