Procockerellia

| Notice: | This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly. This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX: @article{Portman2017ZooKeys, RIS/ Endnote: TY - JOUR Wikipedia/ Citizendium: <ref name="Portman2017ZooKeys">{{Citation See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Ordo: Hymenoptera

Familia: Andrenidae

Name

Timberlake – Wikispecies link – Pensoft Profile

- Perdita (Procockerellia) Timberlake, 1954: 402. Type species: Perdita (Procockerellia) albonotata Timberlake, 1954, by original designation.

- Perdita (Allomacrotera) Timberlake, 1960: 131. Type species: Perdita (Procockerellia) stephanomeriae Timberlake, 1954, by original designation and monotypy. Syn. n.

Subgeneric diagnosis

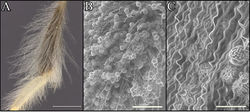

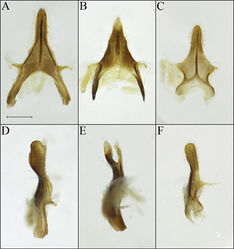

Procockerellia can be recognized by two characters. First, the unique scopal hairs of the female are long, dense, and tightly corkscrew-shaped, appearing kinky or crimped (Fig. 1). Second, the male S8 is apically narrowed into a carinate median keel (Fig. 2), rather than having a club-shaped apical process as found in related and similar subgenera Cockerellia Ashmead, 1898, Hexaperdita Timberlake, 1954, and Pentaperdita Cockerell and Porter, 1899. Callomacrotera Timberlake, 1954 also has a median carina on S8, but the apical process is short and spade-shaped (rather than long and narrow), and the subgenus can be separated by numerous other morphological characters (Timberlake 1954[1]). Procockerellia can be further recognized by having the maxillary palpi 3- or 5-jointed in both sexes, mandibles expanded medially in the females and female pygidial plate truncate, lacking a median emargination. The male hind tarsal claws can be either simple or bidentate.

Biology

Although specimens of Procockerellia have been collected on many plant families (see below), our results support the idea that all the species are specialists on the plant genus Stephanomeria Nutt. (Asteraceae), since only Stephanomeria pollen has been found in the scopae of all three species. Bees are active in the early morning before the flowers close, and may also be active in the evening. The nesting biology is unknown, but they are presumably ground nesting bees like other species of Perdita. Both P. albonotata and P. moabensis are found throughout the flowering season from spring to fall, suggesting they are multivoltine. Thus, the flight period of Procockerellia matches the bloom period of the genus Stephanomeria, which contains species that collectively bloom from spring to fall (Gottlieb 1972[2]). The paucity of collection events renders the phenology of P. stephanomeriae unclear.

Remarks

The relationship between Procockerellia, Allomacrotera and closely-related subgenera is ambiguous, though Prockerellia is clearly a member of the monophyletic group made up of the subgenera Callomacrotera, Cockerellia, Hexaperdita, Pentaperdita and Xeromacrotera Timberlake, 1954 (Danforth 1996[3]). The reduced number of maxillary palpi suggests an affinity to the subgenus Pentaperdita, which has the maxillary palpi 5-jointed (Timberlake 1954[1]). Danforth (1996)[3] suggested a close relationship to Cockerellia, though the species of Procockerellia also bear a general resemblance to the monotypic subgenus Xeromacrotera, which also has an uncertain phylogenetic relationship (Portman et al. 2016a[4]).

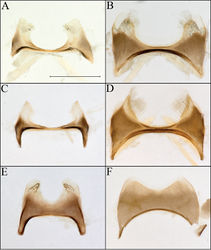

The many similarities in scopal hairs (Fig. 1), morphology, genitalia (Fig. 2), apical sterna (Figs 3, 4), coloration and general gestalt (Figs 5, 6) all support a close relationship between Procockerellia and Allomacrotera that does not justify different subgenera. The structural similarities between S6, S7, and S8 in the males of P. albonotata and P. moabensis suggest that these are sister species, which would render Allomacrotera paraphyletic. In particular, P. albonotata and P. moabensis have S6 and S7 deeply divided and emarginate and S6 with pronounced lateral hair tufts; these characters are lacking in P. stephanomeriae (Figs 3, 4). Timberlake (1980)[5] and Michener (2007)[6] also reported that Allomacrotera lacked lateral furrows in the flanks of the pronotum, but all three species contained in the two subgenera have the flanks of the pronotum moderately impressed. The close relationship between P. albonotata and P. moabensis suggests two possible solutions to fix the classification of Procockerellia and Allomacrotera. Either (1) P. moabensis should be moved from Allomacrotera to Procockerellia, or (2) Allomacrotera and Procockerellia should by merged. If P. moabensis were to be moved to Procockerellia, it would eliminate the sole defining character of Allomactera (bifurcate hind tarsal claws in the male) because both P. moabensis and P. stephanomeriae share this character, while P. albonotata lacks it. In addition, the only remaining character unique to Allomacrotera would be the 3-jointed maxillary palpi. However, we agree with Timberlake (1954)[1] that the reduction of maxillary palpi is more important for classification than the specific number of palpi. Indeed, a similar pattern can be seen in the Halictoides group of subgenus Perdita sensu stricto, which includes incredibly similar species in which the maxillary palpi collectively range in number from one to five (Timberlake 1958[7]). Therefore, we have chosen to synonymize Allomacrotera with Procockerellia due to the shared characters of the corkscrew-shaped scopal hairs (Fig. 1) and keel-shaped apical process of S8 (Fig. 3). The species of Procockerellia are distinctive in Perdita due to their unique scopal hairs, which are especially long, dense, and tightly corkscrew-shaped, appearing crimped under all but the highest magnification (Fig. 1). This type of scopal hair morphology is rare, and to our knowledge only occurs in one other group, the panurgine genus Panurgus Panzer, 1806 (Pasteels et al. 1983[8]). The corkscrew hairs of Procockerellia encircle the hind tibia and basitarsus, and the tips are slightly clavate (Fig. 1C). Scopal hairs are also present on the hind femur and trochanter, though these are minutely branched rather than corkscrew-shaped. Similar to the related subgenera Callomacrotera, Cockerellia, Hexaperdita, Pentaperdita, Xeromacrotera (Danforth 1996[3]), the species of Procockerellia initially pack dry pollen into the scopa and then cap it with pollen that has been moistened with nectar (Timberlake 1954[1], Norden et al. 1992[9], Portman and Tepedino 2017[10]). Pollen loads on museum specimens indicate that P. albonotata and P. moabensis cap approximately the last 20% of the pollen load on the anterior face of the hind tibia with moistened pollen. The pollen on the trochanter, femur, basitarsus, and posterior face of the hind tibia are not moistened. The proportion of moist and dry pollen carried by P. stephanomeriae is unknown due to a lack of specimens with full pollen loads.

The males of Procockerellia vary greatly in size. Similar to many other Perdita, the male head size increases and becomes more quadrate with larger body size (fig. 7, Norden et al. 1992[9], Portman et al. 2016a[4]). However, the distribution of head sizes is continuous, and there are not discrete classes as seen in the Perditini species Macrotera portalis (Danforth 1991[11]). The function of the large, quadrate heads is unknown, though it could be used for inter-male aggression and/or grasping females during mating (Norden et al. 1992[9], Danforth and Neff 1992[12]).

Key to species

Females:

Taxon Treatment

- Portman, Z; Griswold, T; 2017: Review of Perdita subgenus Procockerellia Timberlake (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae) and the first Perdita gynandromorph ZooKeys, (712): 87-111. doi

Images

|

Other References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Timberlake P (1954) A revisional study of the bees of the genus Perdita F. Smith, with special reference to the fauna of the Pacific Coast (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae). Part I. University of California Publications in Entomology 9: 345–432.

- ↑ Gottlieb L (1972) A proposal for classification of the annual species of Stephanomeria (Compositae). Madroño 21: 463–481.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Danforth B (1996) Phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Perdita subgenera Macrotera, Macroteropsis, Macroterella, and Cockerellula (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae). University of Kansas Science Bulletin 55: 635–692.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Portman Z, Griswold T, Pitts J (2016a) Association of the female of Perdita (Xeromacrotera) cephalotes (Cresson), and a replacement name for Perdita bohartorum Parker (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae). Zootaxa 4097: 567–574. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4097.4.8

- ↑ Timberlake P (1980) Supplementary studies on the systematics of the genus Perdita (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae). Part II. University of California Publications in Entomology 85: 1–65.

- ↑ Michener C (2007) The bees of the world. 2nd ed. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 953 pp.

- ↑ Timberlake P (1958) A revisional study of the bees of the genus Perdita F. Smith, with special reference to the fauna of the Pacific Coast (Hymenoptera, Andrenidae). Part III. University of California Publications in Entomology 14: 303–410.

- ↑ Pasteels J, Pasteels J, De Vos L (1983) Ètude au microscope èlectronique à balayage des scopas collectrices de pollen chez les Panurginae (Hymenoptera, Apoidea, Andrenidae). Archives de Biologie 94: 53–73.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Norden B, Krombein K, Danforth B (1992) Taxonomic and bionomic observations on a Floridian panurgine bee, Perdita (Hexaperdita) graenicheri Timberlake (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae). Journal of Hymenoptera Research 1: 107–118.

- ↑ Portman Z, Tepedino V (2017) Convergent evolution of pollen transport mode in two distantly related bee genera (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae and Melittidae). Apidologie 48: 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-016-0489-8

- ↑ Danforth B (1991) The morphology and behavior of dimorphic males in Perdita portalis (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 29: 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00163980

- ↑ Danforth B, Neff J (1992) Male polymorphism and polyethism in Perdita texana (Hymenoptera: Andrenidae). Annals of the Entomological Society of America 85: 616–626. https://doi.org/10.1093/aesa/85.5.616