| Notice: |

This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly.

This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Barney R, LeSage L, Savard K (2013) Pachybrachis (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Cryptocephalinae) of Eastern Canada. ZooKeys 332 : 95–175, doi. Versioned wiki page: 2013-09-19, version 36952, https://species-id.net/w/index.php?title=Pachybrachis&oldid=36952 , contributors (alphabetical order): Pensoft Publishers.

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX:

@article{Barney2013ZooKeys332,

author = {Barney, Robert J. AND LeSage, Laurent AND Savard, Karine},

journal = {ZooKeys},

publisher = {Pensoft Publishers},

title = {Pachybrachis (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Cryptocephalinae) of Eastern Canada},

year = {2013},

volume = {332},

issue = {},

pages = {95--175},

doi = {10.3897/zookeys.332.4753},

url = {http://www.pensoft.net/journals/zookeys/article/4753/abstract},

note = {Versioned wiki page: 2013-09-19, version 36952, https://species-id.net/w/index.php?title=Pachybrachis&oldid=36952 , contributors (alphabetical order): Pensoft Publishers.}

}

RIS/ Endnote:

Wikipedia/ Citizendium:

See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Taxonavigation

Ordo: Coleoptera

Familia: Chrysomelidae

Name

Pachybrachis Chevrolat, 1836 – Wikispecies link – Pensoft Profile

There has been some debate as to the correct spelling of the genus Pachybrachis. Fall’s (1915)[3] monumental work used Pachybrachys Chevrolat and cited its general American usage by J. L. LeConte. However, this emendation was unjustified under the rules of the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN 1999[4], Article 32).

Pachybrachis is a member of the subfamily Cryptocephalinae Gyllenhall, 1813, commonly known as the case bearers due to the fact that all known larval stages live in a case constructed of their fecal matter and often plant debris (LeSage 1985[5]). Their cylindrical, compact body characterizes the adults, which usually have the head retracted into the pronotum to the level of the eyes.

In the recent revision of family-group names in Coleoptera (Bouchard et al. 2011[6]), the former tribe Pachybrachini Chapuis, 1874 was relegated to subtribe under the tribe Cryptocephalini Gyllenhal, 1813. Pachybrachina Chapuis, 1874 contains only two genera north of Mexico, Griburius and Pachybrachis, and is characterized by long filiform antennae, with a marginal bead at the base of pronotum which is not crenulate. Riley et al. (2002)[7] separated the two genera by prosternal charateristics (prosternum broad, as wide as long in Griburius, narrower, longer than wide in Pachybrachis). Additional generic keys can be found in Blatchley (1910)[8], Chagnon and Robert (1962)[9], Downie and Arnett (1996)[10], and Ciegler (2007)[11].

Useful morphological characters. Fall (1915)[3] provided a very detailed “Review of Structural Characters Useful in Taxonomy”, which we will not repeat here. However, there are a few key characters that will be useful to separate the seventeen Canadian species. These features will be described, detailed and illustrated, most of them being used in the identification key.

Size. The seventeen species can generally be divided into four size classes by average length: very small, <1.75 mm; small, >1.75 mm to 2.35 mm; medium, >2.35 mm to 2.85 mm; and large, >2.85 mm to 3.30 mm. Pachybrachis hepaticus is the only species in the very small category, with a mean length of 1.68 mm. Pachybrachis m-nigrum (2.59 mm), Pachybrachis othonus othonus (2.63 mm), and Pachybrachis luridus (2.65 mm) are in the medium category. Pachybrachis trinotatus (3.09 mm) and Pachybrachis bivittatus (3.12 mm) are the only species with males averaging over 3 mm in length. Small is the largest category, with the remaining eleven species. Mean length and width of males are reported for each species. Females are generally larger, thus accounting for the larger overall sizes reported by Fall (1915)[3].

Antennae. In most species (e.g. Pachybrachis atomarius, Habitus 1; Pachybrachis bivittatus, Habitus 2), the length of antennae equals about 2/3 to 3/4 the length of the body. There are two noticeable exceptions. In Pachybrachis hepaticus (Habitus 5) the antennae do not exceed half of the body length, whereas in Pachybrachis trinotatus (Habitus 17) the antennae equal or exceed the body length.

Eyes. The eyes of Pachybrachis pectoralis are close to each other and separated by less than their width (Figure 1a). In most species the distance between the eyes roughly corresponds to their width (e.g. Pachybrachis peccans, Figure 1b). A normal distance between eyes, coupled with the head coloration, can be diagnostic, as in Pachybrachis atomarius that has a largely yellow face (Figure 1c). In Pachybrachis hepaticus, the eyes are very small and markedly remote, separated by much more than their diameter (Figure 1d).

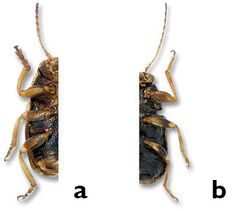

Ocular lines. Many Pachybrachis species have an impressed line, called the ocular line, around the margin of the eyes, and in some species the line diverges from each eye as lines of darker colored punctures between the eyes (e.g. Pachybrachis peccans, Figure 2a). This character is very consistent within each species, and it is easy to see provided the specimens are properly oriented and lighted. In Pachybrachis hepaticus the ocular lines are very short but distinct above the eyes (Figure 2b). In other species, however, such ocular lines are absent (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 2c). Femora. Except for Pachybrachis hepaticus (Figure 3a), the femora on the forelegs of all species (Figure 3b) are incrassate or thickened in relation to the other femora. This character is difficult to see because in most cases legs are folded and pressed tightly against the body. Consequently, it might be necessary to relax the legs and spread them out to compare the front femora with those of the middle and hind legs. When such preparation is achieved, the larger size of the femora becomes evident (e.g. Pachybrachis calcaratus, Habitus 3). Claws. In Pachybrachis, the tarsal claws are all simple (Figures 4a–d), but claws on the forelegs (Figures 4a, b) of several species are distinctly enlarged relative to the claws on the other legs (Figures 4c, d), as in Pachybrachis peccans (Habitus 12) or Pachybrachis pectoralis (Habitus 13). Due to the position of the legs in dead specimens, this character is often easier to see in lateral view (Figures 4c, d) than in front view (Figures 4a, b). Tibial spurs. In Pachybrachis atomarius (Habitus 1), Pachybrachis m-nigrum (Habitus 8), and Pachybrachis trinotatus (Habitus 17), there is no apical spur on front tibia (Figure 5a), but a tuft of large apical setae grouped together may superficially look like a spur. In Pachybrachis spumarius (Figure 5b, Habitus 14) the front tibial spur is very small, hidden and difficult to see, but the very large and exposed front tibial spur is unique and distinctive of Pachybrachis calcaratus (Figure 5c, Habitus 3). In all species, except Pachybrachis hepaticus, the middle tibiae are armed with small slender apical spur (Figure 5d). In all species studied here, the hind tibiae are unarmed. Pronotum. In Pachybrachis, the pronotum is margined at base, the margin usually ornamented with a row of large punctures (Figure 6a, close up). This character is very useful to separate Pachybrachis Chevrolat from Cryptocephalus Geoffroy or Bassareus Haldeman. The last two genera superficially look like Pachybrachis but are not margined at the base of the pronotum. The density and pattern of pronotal punctures can be a useful character. Punctures usually dissipate near the side margins, and are generally a darker color than the background.

The pronotal coloration varies from a common mottled pattern (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 6b), to a black M-mark on a light background (e.g. Pachybrachis m-nigrum, Figure 6c), to an almost entirely black pronotum with only yellow basal and lateral markings (e.g. Pachybrachis nigricornis carbonarius, Figure 6d).

Elytra. As on the pronotum, the density and pattern of punctures on the elytra are easily seen and useful characters. The elytral punctures generally form fairly regular deep striae, consisting of one sutural, one marginal and eight discal striae on each elytron, although the first may be somewhat irregular in the basal third (e.g. Pachybrachis luctuosus, Figure 7a). Punctures may be confused in the basal half but with a tendency towards regular rows in the apical half, as in Pachybrachis calcaratus (Figure 7b). Finally, punctures may be completely confused and not aligned at all in rows (e.g. Pachybrachis hepaticus, Figure 7c). The elytral color pattern is, of course, a very useful character for the identification of many species. The mottled pattern is common (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 7d). Some species are vittate (= with longitudinal black stripes), sometimes with a lateral vitta interrupted as in Pachybrachis bivittatus (Figure 7e). In some species, the elytra are largely black with only a few yellow markings or with narrow apical and lateral margins (e.g. Pachybrachis nigricornis carbonarius, Figure 7f), or the elytra can be entirely black (e.g. Pachybrachis luridus, Figure 7g).

Pygidium. The coloration of the pygidium can be largely yellow (e.g. Pachybrachis bivittatus, Figure 8a), dark with distinct yellow spots of various sizes (e.g. Pachybrachis cephalicus, Figure 8b), or dark with faint small reddish spots (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 8c). A completely black pygidium is distinctive of Pachybrachis atomarius (Figure 8d). Sexes. Males are usually smaller and less robust than females, with their abdomen flat (Figure 9a). In females, the abdomen is convex beneath, the last visible segment having a deep, round, concave depression or fovea (Figure 9b). Genitalia. In most cases, individuals of each sex can be identified to species using coloration and external morphological features alone. However, an examination of the aedeagus is essential for the determination of superficially similar and variable species, such as Pachybrachis cephalicus, Pachybrachis luctuosus and Pachybrachis spumarius.

In Pachybrachis, the basal portion of the aedeagus may appear bulbous (e.g. Pachybrachis luctuosus, Figure 10a) or more tubular (Figure 10b), but we don’t know yet if this character is reliable and consistent. The apical half is usually considerably bent, sometimes at a right angle, the degree of the curvature being an important diagnostic feature. In lateral view, the tip of the aedeagus may appear straight, sinuous and curved upwards, or sinuous and curved downwards (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 10b). In dorsal view, the tip offers various shapes: small, large, pointed, triangular, lanceolate, nipple-shaped (e.g. Pachybrachis spumarius, Figure 10c), etc. Although the genitalic features are very constant and most reliable, they have been rarely described and illustrated in Pachybrachis. In the following key to the males of the 17 species treated here, the aedeagus is reported for only three species when external morphological characters may not be sufficient. The female genitalia are still unknown for all of them.

Illustrated key to males

Taxon Treatment

- Barney, R; LeSage, L; Savard, K; 2013: Pachybrachis (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae, Cryptocephalinae) of Eastern Canada ZooKeys, 332: 95-175. doi

Other References

- ↑ Jacoby M (1908) Fauna of British India, including Celyon and Burma. Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae. Volume 1. Taylor and Francis, London, 534 pp.

- ↑ Mannerheim C (1843) Beitrag zur Käferfauna der Aleutischen Inseln, der Insel Sitka und Neu-Californiens. Bulletin de la Société Impériale des Naturalistes de Moscou 16: 175–314.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Fall H (1915) A revision of the North American species of Pachybrachys. Transactions of the American Entomological Society 41: 291-486.

- ↑ ICZN ( (1999) International code of zoological nomenclature. Fourth Edition. International Trust for Zoological Nomenclature, London, 306 pp.

- ↑ LeSage L (1985) The eggs and larvae of Pachybrachis peccans and P. bivittatus, with a key to the known immature stages of the nearctic genera of Cryptocephalinae (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). The Canadian Entomologist 117: 203-220. doi: 10.4039/Ent117203-2

- ↑ Bouchard P, Bousquet Y, Davies A, Alonso-Zarazaga M, Lawrence J, Lyal C, Newton A, Reid C, Schmitt M, Slipinski S, Smith A (2011) Family-group names in Coleoptera (Insecta). Zookeys 88: 1-972. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.88.807

- ↑ Riley E, Clark S, Flowers R, Gilbert A (2002) Family 124. Chrysomelidae Latreille 1802. In: Arnett R Thomas M Skelley P Frank J (Eds) American Beetles. Volume 2. Polyphaga: Scarabaeoidea through Curculionoidea. CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, Florida, 617–691.

- ↑ Blatchley W (1910) An illustrated descriptive catalogue of the Coleoptera or beetles (exclusive of the Rhynchophora) known to occur in Indiana – with bibliography and descriptions of new species. The Nature Publishing Co., Indianapolis, Indiana, 1386 pp. doi: 10.5962/bhl.title.56580

- ↑ Chagnon G, Robert A (1962) Principaux Coléoptères de la province de Québec. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, Montréal, Québec, 440 pp.

- ↑ Downie N, Arnett R (1996) The Beetles of Northeastern North America. Volume II. Polyphaga: Series Bostriciformia through Curculionidea. The Sandhill Crane Press, Gainesville, Florida, 831 pp.

- ↑ Ciegler J (2007) Leaf and seed beetles of South Carolina (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae and Orsodacnidae). Biota of South Carolina 5: 1-246.

Images

| Figure 4. Claws: a, b front claws enlarged c, d normal. |

|