Apodrosus zayasi

| Notice: | This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly. This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX: @article{Anderson2017ZooKeys, RIS/ Endnote: TY - JOUR Wikipedia/ Citizendium: <ref name="Anderson2017ZooKeys">{{Citation See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Ordo: Coleoptera

Familia: Curculionidae

Genus: Apodrosus

Name

Apodrosus zayasi Anderson sp. n. – Wikispecies link – ZooBank link – Pensoft Profile

Specimens examined

1 male, 2 females. Holotype male (CMNC), labelled CUBA: Province Cienfuegos, Parque Nacional Pico San Juan, road, 21.98812, -80.14632, 1086 m, 19.V.2013, R. Anderson, 2013-022X, hand collections. Paratype. Data as holotype (1 female; CMNC). Pico San Juan, near peak, 21.9886833, -80.1465833, 1105 m, 19.V.2013, G. Zhang, CB-13, L.22 (1 female; ASUHIC).

Diagnosis

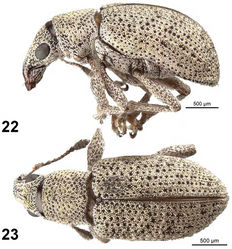

This species is distinguished from other Cuban species by the eyes small, rounded, the distance from posterior margin of eye to posterior margin of head about the same as greatest diameter of an eye, and by distinctive male genitalia. It is the only Cuban species with such small, rounded eyes.

Description

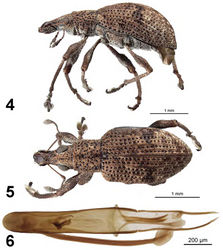

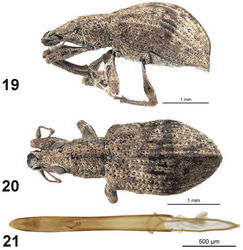

Male. Body length 3.6 mm; in dorsal view about 2.3 times longer than greatest width which is at about second third of elytra; dorsal outline in lateral view quite tumid. Vestiture composed of pale to dark brown scales, with very small recurved, fine brown setae. Eyes 1.1 times longer than wide, projected, separated from anterior margin of prothorax by about greatest diameter of eye; line of anterior margin of eyes very slightly impressed; shortest distance between eyes (dorsal view) 0.5 times greatest width of pronotum; median furrow linear, narrow and shallow, extending from anterior margin of eyes but not reaching anterior margin of pronotum, partially obscured by scales. Rostrum slightly longer than wide; epistoma apically with two setae situated on each side; nasal plate well defined, v-shaped, slightly tumid, not declivious. Antennal insertion apicad of midpoint of rostrum; scrobe curved downwards by 45°, directed posteriorly at end, barely reaching anterior margin of eye, separated from it by 2.0 times width of scrobe. Mandibles with 2 lateral setae. Antennae reddish brown; antennal scape extending to just slightly beyond posterior margin of eye; desmomere I about same length as II. Pronotum cylindrical, slightly wider than long, greatest width at midlength; dorsal surface shallowly punctate but largely obscured by scales, each puncture with a curved, fine brown seta; posterior margin slightly bisinuate, slightly wider than anterior margin; scutellum subcircular, glabrous. Mesocoxal cavities about 5 times width of intercoxal process. Metasternum with lateral portions slightly tumid, not posteriorly produced. Elytra in dorsal view 1.8 times their greatest width; anterior margin sinuate; humeral region of elytra 1.5 times width of posterior margin of pronotum; lateral margins slightly divergent until second third, thereafter convergent; apex acutely rounded; in lateral view with dorsal outline tumid; posterior declivity gradually descending; stria 9 complete, stria 10 interrupted above metacoxa (appearing to merge with stria 9), resuming at suture between ventrites 1 and 2; intervals completely covered with scales, with dark and light areas forming an irregular pattern; all intervals equally flat, humerus angled; interval 9 very slightly tumid above metacoxa; all intervals with recurved, fine brown setae. Venter with scales very sparse, linear and hair-like on all ventrites; ventrites 3 and 4 subequal in length, their combined length shorter than ventrite 5; posterior margin of ventrite 5 widely rounded, finely narrowly emarginate at middle, apex at middle narrowly impressed. Tegmen with tegminal apodeme 0.8 times length of aedeagus; tegminal plate simple. Aedeagus short and robust, in dorsal view about 3.0 times longer than its greatest width; apex rounded, deflexed ventrally. Endophallus extended to just beyond base of aedeagus, with no visible internal sclerotization. Aedeagus in lateral view slightly evenly convex. Aedeagal apodemes about same length as aedeagus.

Female. Body length 3.4–3.6 mm.

Etymology

This species is named after Fernando de Zayas (1912–1983), entomologist, Cuban Academy of Sciences.

Natural history

Adults were collected beating vegetation along the upper part of the road to Pico San Juan.

Key to Cuban species of ApodrosusPhylogeny and biogeographic implications A distribution map of Cuban Apodrosus is shown in Fig. 27. The 33-taxon molecular phylogeny (Suppl. material 2), reconstructed using a maximum likelihood method, recovers the monophyly of Apodrosus (bootstrap value 100%) represented by 11 species in the current study. Apodrosus and Polydrusus are recovered as sister groups, although with poor nodal support. In other words, the monophyly of Polydrusini as sampled in the current study is recovered. It is worth pointing out that numerous genera of this tribe are not sampled here and the phylogenetic coherence or monophyly of Polydrusini remain to be fully tested. Most critically, Anypotactus, sister group of Apodrosus recovered by Girón and Franz (2010)[1] was not sampled here. It would be premature to draw a conclusion on the placement of Apodrosus. Pachyrhinus lethierryi is nested within Polydrusus, necessitating the synonymy of the two genera, but this question is left for future investigations. The 13-taxon Apodrosus focal phylogeny is congruent with the 33-taxon phylogeny in the “deeper” relationships within Apodrosus, but the two differ in relationships among five Cuban species (A. zayasi–A. mensurensis clade in Fig. 28). We will base our phylogenetic and biogeographic discussions on the 13-taxon phylogeny, as our biogeographic discussions primarily concern inter-island patterns and the phylogenetic resolution within Cuban species is inconsequential in that regard.We recognize that bootstrap nodal support values are low for several clades, reflecting potential inconsistency in the data. We opted for presenting a fully dichotomous phylogeny, as is the case in many publications. Biogeographic scenarios are discussed in light of this dichotomous phylogeny (which is the best phylogeny available), but it is understood that they also are subject to future testing and revisions when additional data is acquired. Apodrosus argentatus Wolcott, 1924, a widespread species distributed in both Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, is recovered as sister to the remaining species of Apodrosus. The six Cuban species sampled here are not monophyletic. Five of the Cuban species form a clade (A. zayasi–A. mensurensis), which is sister to an unidentified species from Dominican Republic (which might represent a new species as it could not be keyed out using Girón and Franz 2010[1]). A single species, Apodrosus alternatus, forms a sister relationship with A. quisqueyanus Girón & Franz, 2010, a species from the Dominican Republic. Together, they are part of a larger clade that also includes two Puerto Rican species, A. wolcotti and A. epipolevatus Girón & Franz, 2010.

The current molecular phylogeny (Fig. 28) and the morphological phylogeny by Girón and Franz (2010)[1] differ in taxon sampling, but congruence and conflict between these phylogenies can be observed and are presented as follows. Apodrosus wolcotti and A. epipolevatus, both from Puerto Rico, are sister species in both analyses. In Girón and Franz (2010)[1], A. quisqueyanus is more closely related to A. argentatus than either is to the two Puerto Rican species. In contrast, the current phylogeny posits a closer relationship between A. quisqueyanus and the Puerto Rican species, which are in the same clade, whereas A. argentatus is outside that clade.

According to the current phylogenetic hypothesis (Fig. 28), species of Apodrosus from the same island are distributed in multiple clades and some sister groups are formed by species from different islands. This pattern of the geographic distributions of species of Apodrosus with regards to the phylogeny is reminiscent of other Caribbean entimines (Zhang et al. 2017[2]), and is indicative of multiple successive dispersal events between islands. A “stepping-stone” scenario of an origin in Puerto Rico and subsequent dispersal to Hispaniola and Cuba is plausible. An alternative explanation of the biogeographic pattern is island to island vicariance. According to the geological evolution model proposed by Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee (1999)[3], the three Greater Antillean islands, Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, were connected to form a landspan in the Late Eocene and Early Oligocene (35–33 million-years ago [Ma]). Eastern Cuba and northern Hispaniola were physically connected during the Early Oligocene, which split apart later in that epoch. On the other hand, central Hispaniola and Puerto Rico remained connected probably until late in the Miocene (14 Ma). A sister relationship between Cuba and the Dominican Republic appears twice in our phylogeny, which is in accordance with the vicariance of the two islands. However, in the clade “A. epipolevatus–A. alternatus”, Puerto Rico is sister to Cuba and the Dominican Republic, implying an early split of Puerto Rico from the two larger islands, which is at odds with the vicariance model proposed by Iturralde-Vinent and MacPhee (1999)[3] (i.e., a late split between Puerto Rico and Hispaniola).

Original Description

- Anderson, R; Zhang, G; 2017: The genus Apodrosus Marshall, 1922 in Cuba (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Entiminae, Polydrusini) ZooKeys, (679): 77-105. doi

Images

|

Other References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Girón J, Franz N (2010) Revision, phylogeny, and historical biogeography of the genus Apodrosus Marshall, 1922 (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Entiminae). Insect Systematics & Evolution 41: 339–414. dx.https://doi.org/10.1101/053611

- ↑ Zhang G, Basharat U, Matzke N, Franz N (2017) Model selection in statistical historical biogeography of Neotropical weevils – the Exophthalmus genus complex (Insecta: Curculionidae: Entiminae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 109: 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2016.12.039

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Iturralde-Vinent M, MacPhee R (1999) Paleogeography of the Caribbean region: Implications for Cenozoic biogeography. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 238: 3–95. hdl.handle.net/2246/1642