Echinodon becklesii

Contents

- 1 Taxonavigation

- 2 Name

- 3 Lectotype

- 4 Paralectotypes

- 5 Type locality

- 6 Horizon

- 7 Derivation of the name

- 8 Revised diagnosis

- 9 Description

- 10 Premaxilla

- 11 Maxilla

- 12 Lacrimal and jugal

- 13 Palatine and ectopterygoid

- 14 Predentary

- 15 Dentary

- 16 Premaxillary teeth

- 17 Maxillary teeth

- 18 Dentary teeth

- 19 Skull reconstruction

- 20 Taxon Treatment

- 21 Images

- 22 Other References

| Notice: | This page is derived from the original publication listed below, whose author(s) should always be credited. Further contributors may edit and improve the content of this page and, consequently, need to be credited as well (see page history). Any assessment of factual correctness requires a careful review of the original article as well as of subsequent contributions.

If you are uncertain whether your planned contribution is correct or not, we suggest that you use the associated discussion page instead of editing the page directly. This page should be cited as follows (rationale):

Citation formats to copy and paste

BibTeX: @article{Sereno2012ZooKeys226, RIS/ Endnote: TY - JOUR Wikipedia/ Citizendium: <ref name="Sereno2012ZooKeys226">{{Citation See also the citation download page at the journal. |

Ordo: Ornithischia

Familia: Heterodontosauridae

Genus: Echinodon

Name

Echinodon becklesii Owen, 1861 – Wikispecies link – Pensoft Profile

- Echinodon becklesii Owen, 1861 – Owen (1861[1], pl. 8, Figs 1, 2); Owen (1874[2], pl. 2, fig. 22); Galton (1978[3], Figs 1, 2J-O); Galton (1986[4], 16.6b-e); Benton and Spencer (1995[5], fig. 7.16e); Galton (2007[6], Figs 2.6I-K, 2.7H-K); Norman and Barrett (2002[7], Figs 7, 8, pls. 1, 2)

Lectotype

NHMUK 48209 (Figs 11, 13C, D, part of the left and right premaxillae, anterior part of left maxilla with the caniniform tooth and maxillary teeth 2 and 3, and an impression of the lateral aspect of the posterior ramus of the maxilla and maxillary teeth 4 and 5; NHMUK 48210 (Figs 13A, B, 14), posterior ramus of the maxilla with 6 alveoli and 5 complete or partial crowns, the ventral end of the left lacrimal, the anterior end of the left jugal, and most of the left ectopterygoid. Both specimens belong to the anterior end of a single, partially disarticulated snout embedded in a block that split between the maxillae during, or shortly after, its collection (Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, Figs 1, 2; Galton 1978[3]: Figs 1A, B; Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: pl. 1, Figs 1, 2).

Paralectotypes

NHMUK 48211 (Fig. 12), partial right maxilla with maxillary teeth 2-7 with the tip of the right jugal and part of the right palatine; NHMUK 48212, partial right maxilla with 6 teeth; NHMUK 48213 (Fig. 18), partial left dentary with 8 alveoli and 7 teeth; NHMUK 48214, partial right dentary without teeth; NHMUK 48215a, right dentary with 10 alveoli and 9 teeth; NHMUK 48215b (Figs 15–17), left dentary with 10 alveoli and 5 teeth.

Referred material. NHMUK 48229, jaw fragment; NHMUK 40723, dentary fragment; DORCM GS 1164-5, 1167, 1171, 1194, 1212-6, 1222-3, isolated teeth.

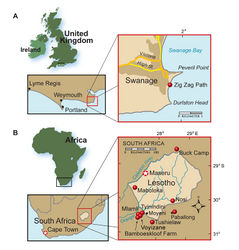

Type locality

“Mammal Pit” located high on the coastal cliff section near the Zig Zag Path at Durlston Bay, Isle of Purbeck, Dorset, southern England (Fig. 1A); N50°35', W1°55' (Melville and Freshney 1982[9]; Salisbury 2002[10]).

Horizon

Either the Marly or the Cherty Freshwater Member, Middle Purbeck Beds of the Purbeck Formation; Lower Cretaceous, Berriasian, ca. 146-140 Ma (Owen 1861[1]; Clements 1993[11]; Salisbury 2002[10]; Gradstein and Ogg 2009[12]). Although Galton (1978[3]: 151) stated that the lectotype and paralectotype material came from the Mammal Bed (= “dirt bed”; Durlston Bay 83) of the Middle Purbeck Beds (Marly Freshwater Member), no evidence exists to link the fossils to that particular horizon. They may have come from the Feather Bed (Durlston Bay 108) slightly higher in the section (Cherty Freshwater Member).

Derivation of the name

The species name becklesii, coined by Owen (1861[1]: 35)after Samuel H. Beckles who found the fossils, has been misspelled several ways in the literature (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]), first as “becclesii” by Owen himself (1861[1]: pl. 8) and later as “becklesi” (Lydekker 1888[13]) and “becklessii” (Galton 1978[3]). S. H. Beckles spelled his surname with a “k” (e.g., Beckles 1854[14]), although variants on his surname have persisted as well (e.g., “Beccles”; Salisbury 2002[10]).

Revised diagnosis

Heterodontosaurid ornithischian characterized by the following six autapomorphies: (1) slender, nearly straight caniniform first maxillary tooth with unornamented anterior and posterior carinae; (2) edentulous anterior dentary margin (as long as two alveoli); (3) only 9 dentary teeth posterior to the caniniform tooth; (4) dentary crowns in the middle of the tooth row that are proportionately taller than opposing maxillary crowns (the apical 50% of middle dentary crowns are denticulate versus 25% of mid maxillary crowns); (5) anteroposteriorly elongate dentary symphysis (maximum length approximately 3 times maximum depth); (6) symphyseal flange ventral to primary dentary symphysis.

Description

The original description of Echinodon becklesii is insightful and accurate in most regards (Owen 1861[1]: 35–39, pl. 8). During the ensuing 150 years, the specimens have undergone further preparation and also have sustained some damage and loss (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: 173). Only a few new fragments and isolated teeth have come to light that may be tentatively referred to Echinodon becklesii (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]), and so further information about this heterodontosaurid depends on the original materials. This review attempts to bring together published information and figures (Owen 1861[1]; Galton 1978[3]; Sereno 1991[15]; Norman and Barrett 2002[8]) and new observations on Echinodon in order to resolve conflicting statements and gain a better understanding of its morphology and status as a heterodontosaurid. The initial interpretation of Echinodon as a heterodontosaurid (Sereno 1991[15], 1997) was based on several of the observations documented below.

Premaxilla

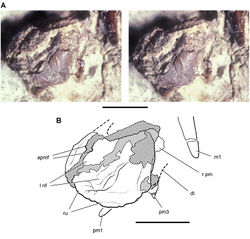

The ventral portions of the left and right premaxillae were originally preserved in mutual articulation in NHMUK 48209 (Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, fig. 1; Galton 1978[3]: fig. 1A; Fig. 13C, D). Galton (1978[3]: 140, fig. 1J) removed the left premaxilla (accidentally identifying it as the left “maxilla”) to expose the palate of the right premaxilla (also Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: pl. 1, fig. 1). The premaxillae are figured here in their original position disarticulated from the associated left maxilla, both lacking anterodorsal and posterodorsal processes (Figs 11, 13C, D).

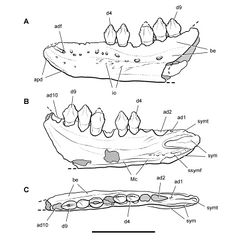

Despite two diagonal fractures and some crushing, several details of the left premaxilla have not been described previously. An anterior premaxillary foramen is present and split in two by a fracture with each half slightly separated (Fig. 11). The anterior premaxillary foramen is a good landmark for the anterior margin of the narial fossa, which is preserved as a broad depression extending ventrally from the foramen toward the a rugose rounded alveolar margin. The location of the anterior premaxillary foramen and ventral extension of the narial fossa is very similar to that in Heterodontosaurus but unlike the configuration in some other ornithischians such as Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a[16]). The rugose anterior portion of the alveolar margin is edentulous, such that the first premaxillary tooth is set in from the front margin of the premaxilla by a distance equal to two or three alveoli (Fig. 11). The edentulous margin was previously reconstructed (Galton 1978[3]: fig. 2J) somewhat shorter in length (Fig. 19A). The longer edentulous margin more closely resembles the condition in Heterodontosaurus and some neornithischians than in basal ornithischians such as Lesothosaurus (Sereno 1991[15]), in which the margin is only approximately one alveolus in length.

The posterior end of the alveolar margin is broken away along with part of the root of the third premaxillary tooth, as the specimen is now preserved (Fig. 11). When this portion of the premaxilla is preserved in other heterodontosaurids, it forms the anterior portion of an arched diastema with an inset medial wall. A similar recessed wall appears to be present on the left premaxilla in Owen’s figure (Fig. 13C, D), but this portion of the bone was broken away by the time Galton figured the specimen (1978[3]: fig. 1A, A’; Fig. 11).

The dorsal portion of right and left premaxillae is broken away. Owen (1861[1]: 36) remarked that part of the “boundary of the external nostril” (= external nares) is preserved, but this does not appear to be a natural margin (Fig. 11). The right premaxilla (exposed with removal of the left premaxilla) preserves a flat palatal surface as mentioned by Galton (1978)[3] and Norman and Barrett (2002)[8]. A relatively flat secondary palate, however, is common among basal ornithischians and likely primitive (e.g., Lesothosaurus; Sereno 1991[15]).

Finally, the position of the premaxilla relative to the maxilla is unknown, as the premaxillae are disarticulated and displaced anteroventral to the maxillae in the only partial cranium known for Echinodon (NHMUK 48209; Fig. 13C, D). The anteromedial process of the left maxilla (now only an impression) lies just above the palatal surface of the right premaxilla, not far from its original articulation. Tooth impressions figured by Owen suggest that a dentary was originally present immediately below the maxillary tooth row (Fig. 13C, D). None of the preserved dentary tooth rows have a crown configuration that matches these impressions. This missing dentary, if present, must have been lost during, or shortly after, collection of NHMUK 48209.

Thus it is likely that much of the anterior end of the snout was originally preserved in NHMUK 48209. In Heterodontosaurus, Abrictosaurus, and Tianyulong, the end of the snout is preserved intact, and the premaxillary alveolar margin is offset ventral to that of the maxilla. In an initial reconstruction of Echinodon, the alveolar margin of the premaxilla was drawn offset dorsally to that of the maxilla (Fig. 19A). The preserved location and form of the premaxilla in Echinodon (NHMUK 48209), to the contrary, suggests that there may have been some ventral offset of the premaxillary alveolar margin as in other heterodontosaurids (Fig. 19B).

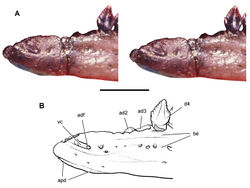

Maxilla

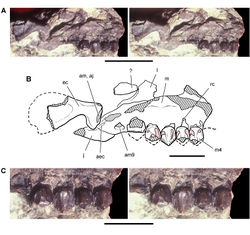

. The maxilla is known from three individuals, including the lectotypic left maxilla (NHMUK 48209, 48210; Figs 13, 14) and two partial right maxillae (NHMUK 48211, 48212; Fig. 12). These specimens allow a more complete description of this bone. Preserved sutural contacts of the maxilla include the premaxilla anteriorly, the lacrimal dorsally, the jugal posteriorly, and the palatine and ectopterygoid medially, (Figs 12–14). A buccal emargination, or cheek embayment, is present along the entire length of the tooth row (Fig. 12). The emargination has been described as “shallow” (Galton 1978[3]: 140), “gentle” (Sereno 199: 1761), and “very shallow” (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: 177). Galton (1978[3]: 140, fig. 1G’) described and identified the upper border of the buccal emargination as a “slight horizontal ridge just above the tooth row”, and this is doubtless the eminence understood to define the upper boundary of the embayment by all three of the authors cited.

Close inspection of the single maxilla exposing this feature, however, casts doubt on this interpretation (NHMUK 48211; Fig. 12). A gently arched row of neurovascular foramina opens within the ornithischian buccal emargination on the maxilla. In Heterodontosaurus this row of foramina is present dorsally near the everted upper rim of the maxilla ventral to the antorbital fenestra. The row of large foramina in the maxilla in Echinodon represents the same neurovascular openings, which are located ventral to the margin of the antorbital fenestra. The maxilla thus has been flattened postmortem, reducing the depth of the buccal emargination. This transverse compression also has partially collapsed the internal canals associated with the row of foramina and reduced the eversion of the ventral margin of the antorbital fenestra. The opposing dentary emargination has deep proportions and includes a row of neurovascular foramina near the edge of the emargination (Figs 16, 17). The maxilla of Echinodon, in sum, appears to have had a buccal emargination (Fig. 19B) similar to that in Heterodontosaurus (Crompton and Charig 1974) and Lycorhinus (Gow 1990[17]).

The anterior end of the same maxilla provides key evidence for the presence of an arched diastema to accommodate the apical end of a lower caniniform tooth (Fig. 13C, D). The laterally protruding, rounded, arched rim of the diastema is clearly preserved and is very similar to that in Heterodontosaurus. Ventral to that rim, the maxilla is inset and forms the posterior portion of a fossa within the diastema for reception of the tip of a dentary caniniform tooth. The margin of the maxilla within the fossa is not complete (contra Galton 1978[3]: fig. 1G’). The short section of this margin that is preserved indicates that it arched above the maxillary tooth row as in Heterodontosaurus and Lycorhinus (NHMUK RU A100). The anterior end of the left maxilla (NHMUK 48210) may have originally included the region of the diastema (Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, fig. 1), but this region is broken away anterior to the first caniniform tooth (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: pl. 1, fig. 1).

Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: 182) criticized my previous observation of an arched diastema in Echinodon (Sereno 1997[18]), stating “it is impossible to determine whether the premaxilla-maxilla diastema was arched” and that a diastema of any kind is “absent from the available material of Echinodon”. Enough of this region is preserved in NHMUK 48211 to remove any doubt that an arched diastema is present in Echinodon (Fig. 12), despite the loss of bone fragments and crowns from two of the maxillae since Owen figured them.

Lacrimal and jugal

Portions of both of these bones are preserved attached to two of the maxillae. In NHMUK 48210, the ventral ramus of the left lacrimal, including a portion of the orbital margin, is preserved posterodorsal to the left maxilla (Fig. 13A, B; Galton 1978[3]: fig. 1G’). This portion of the lacrimal was identified previously as the “ascending process” of the maxilla (Norman and Barrett 2002[8]: fig. 14A).

The anterior end of the jugal is preserved in articulation in two specimens. The first is preserved posterior to the antorbital fenestra (Fig. 12C, D; NHMUK 48211), and the second is located at the posterior end of the maxilla (Fig. 13A, B; NHMUK 48210). This portion of the jugal was identified previously as the “overhanging part of maxilla forming the base of lower temporal bar” (Galton 1978[3]: fig. 1B’).

Palatine and ectopterygoid

The right palatine is preserved in partial disarticulation from its lateral contact with the maxilla (Fig. 12C, D; NHMUK 48211). It appears to have rotated dorsally from its natural articulation exposing its ventral surface. The posterior margin has an embayment for a palatal fenestra.

In NHMUK 48210 the palatal bone posteromedial to the maxilla may be a left ectopterygoid. Immediately adjacent to this bone is an articular scar running across the maxilla-jugal suture. This is the lateral anchor for the ectopterygoid in many ornithischians (Fig. 13A, B). The posteromedial margin of the bone is preserved as an impression, the principal exposed surface is concave, and one of its margins is rounded and thickened as seen in cross-section. The position of the bone and its features best match that of an ornithischian ectopterygoid, a tentative identification. Galton (1978[3]: 140, fig. 1B’) identified this bone as a right quadrate with a “twisted” shaft and “incomplete” distal condyles; Owen (1861[1]: 37) and Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: fig. 7B) identified the bone as the left pterygoid. The potential identifications of this bone could be tested by exposure of its opposing side, which is currently obscured by matrix, or via computed tomographic imaging.

Predentary

Although the predentary is unknown in Echinodon, its presence is indicated by features on the anterior end of the dentary (Fig. 16A). A large anterior dentary foramen opens anteriorly and passes into an anterodorsally inclined, impressed vessel tract. In other ornithischians, this foramen provides passage for the principal vascular supply to the predentary (e.g., Lesothosaurus; Sereno 1991[15]). The predentary in most ornithischians has lateral and ventral processes, and the vascular supply enters the bone near the junction between these processes. In Echinodon the vascular tract is deeply incised in a similar location, which is also the case in Fruitadens (Figs 9A, 17).

The anterior end of the dentary in Echinodon is intermediate between the condition typical of ornithischians (e.g., Lesothosaurus, Hypsilophodon; Sereno 1991[15]; Naish and Martill 2001[19]) and that in most heterodontosaurids. In the former, the end of the dentary is V-shaped, with articular surfaces for the lateral and ventral processes facing dorsally (or dorsomedially) and ventrolaterally, respectively. In most heterodontosaurids, in contrast, the end of the dentary is slightly expanded dorsoventrally and has a single well-defined, arcuate predentary articular surface that faces anterolaterally. In Echinodon the anterior end of the dentary is more rounded than in Lesothosaurus (Sereno 1991[15]) or Hypsilophodon (Naish and Martill 2001[19]) but lacks a well-defined, arcuate articular surface for the predentary.

The dentary does not have a well-defined surface dorsal to the foramen for articulating with the predentary, and so a projecting lateral predentary process probably was not present. The ventral aspect of the anterior end of the dentary has as a subtle smooth articular facet (Figs 15–17). It is not as well marked as in basal ornithischians, where the ventral edge of the dentary is strongly beveled for the median ventral process (e.g., Lesothosaurus; Sereno 1991[15]). Nor is it comparable to that in some heterodontosaurids such as Heterodontosaurus, in which the articular surface for the predentary is well-defined and trough-shaped. Several small neurovascular foramina are present between dorsal and ventral articular areas for the predentary, an area that clearly would not have been covered by the predentary (Fig. 17). In sum, the predentary in Echinodon appears to have a fairly loose articular relation with the dentaries. Previously Galton (1978[3]: Figs 1C’, 2J) inferred the presence of a predentary in Echinodon but misinterpreted the anterior dentary foramen and its associated impressed vessel channel as an articular slot for a prong-shaped lateral predentary process (Fig. 19A). Although a lateral predentary process is present in Hypsilophodon (Galton 1974a[16]: fig. 10) and other ornithischians, the dentary in Echinodon does not show a facet for such a process. Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: 177) stated that they could not locate any articular surface for the ventral predentary process, but a smooth, flattened articular surface runs along the anteroventral edge at the anterior end of both right and left dentaries (Fig. 17).

Dentary

The dentary is best known from paired right and left sides (Figs 15–17; NHMUK 48215a, b) and partial left and right dentaries (NHMUK 48213, 48214). Originally exposed on slabs of rock, all four dentaries were prepared free of matrix prior to their re-description by Galton (1978)[3]. Only a fragmentary dentary has survived from a fourth specimen, which originally included a portion of the left lower jaw (Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, Figs 6–8; NHMUK 48214).

The dentary in Echinodon has particularly stout proportions, even when compared to other heterodontosaurids. Its depth at mid-length is approximately 30% of its length (from anterior extremity to the anterior margin of the external mandibular fenestra) and approximately 40% of the length of the postcaniniform tooth row (Figs 15A, C, 16A, C). In lateral view, the anterior end of the dentary has a subtriangular shape with a strongly beveled anteroventral margin for contact with the predentary (Fig. 17). The middle section of the denary ramus is nearly parallel-sided, expanding only slightly in depth posteriorly. An arched row of relatively large neurovascular foramina opens along the ventral margin of a deep buccal emargination. As in other heterodontosaurids, this emargination tapers in depth near the alveolus for the caniniform tooth in advance of the anterior end of the dentary (Figs 15A, 16A, 17).

The coronoid process is distinctly expanded at mid-length, resulting in a diamond-shaped, rather than tapered, process (NHMUK 48215a, 48213; Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, fig. 8; Galton 1978[3]: fig. 1D; Barrett 2002: pl. 2, fig. 3). The central axis of the coronoid process angles posterodorsally at about 45° to the long axis of the dentary, as best preserved in NHMUK 48215b and NHMUK 48213 (Fig. 19B). Postmortem crushing has increased the inclination of the coronoid process in one dentary (NHMUK 48215a). In basal ornithischians such as Lesothosaurus (Sereno 1991[15]), in contrast, the coronoid process is narrow and tapered (finger-shaped) in lateral view, and the coronoid process is less strongly upturned, angling posterodorsally at about 30°.

The symphysis at the anterior end of the dentary is V-shaped (Figs 15B, 16B). The main articular surface is an oval, raised and textured platform with its long axis horizontal. This articular surface is located almost entirely anterior to the dentary caniniform tooth rather than directly ventral to the caniniform tooth as in Heterodontosaurus. A subtriangular fossa lies between the main symphyseal articulation and a secondary flat symphyseal surface, which is located along the ventral margin. This flat surface may have served as a median buttress or stop, as it is not textured for ligament attachment like the main symphyseal surface.

The anterior ends of the dentary are not inturned to form a spout shape as in most ornithischians. The symphysis in Echinodon, nevertheless, does not lie on the medial plane of the dentary ramus, but rather is elevated from that plane toward the midline. As a result, there is a narrow dorsoventrally concave surface dorsal to the symphysis and medial to the mesialmost teeth (Figs 15C, 16C). A narrow trough-shaped surface thus is present dorsal to the symphysis as in Heterodontosaurus. The symphysis also projects medially in Lycorhinus (NHMUK RU A100) and Heterodontosaurus (SAM-PK-K1332). The main derived features in Echinodon include the elongate symphyseal area, the anterior position of the symphysis relative to the dentary tooth row, and the accessory ventral symphyseal surface near the ventral margin of the dentary.

Galton (1978[3]: 140, fig. 1C’) described and figured the buccal emargination of the dentary as a “small cheek” excluding the row of major neurovascular foramina. Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: 177) also described the buccal emargination of both the dentaries and maxillae as “very shallow.” Transverse compression of several of the dentaries, however, has reduced the depth of the emargination, which must incorporate the principal row of neurovascular foramina. An area of impressed ornamentation is present just below the row of neurovascular foramina, suggesting the presence of tightly adhering integument below the buccal emargination (Figs 15A, 16A).

Galton (1978[3]: 140) described the coronoid process as “prominent”, whereas Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: 177) described it as “low”. One very appropriate comparison is the basal ornithischian Lesothosaurus (Sereno 1991[15]: fig. 13F). Echinodon more closely resembles the more strongly upturned, transversely expanded process in Heterodontosaurus (see below) than the tapered process of shallow inclination in Lesothosaurus (Fig. 19B).

Premaxillary teeth

There are three premaxillary teeth in middle and posterior portions of the premaxilla, preceded by an edentulous margin several alveoli in length (Figs 11, 19B). The first and third crowns are preserved with some breakage and loss since Owen first figured them (Fig. 13C, D). Only small fragments of root and crown of the second tooth remain, the base of which was originally preserved. The crowns are slightly swollen, the mesial side of the crown base more bulbous than the distal side, and have smooth surfaces without denticles or serrations. The crowns are gently recurved with apices set slightly distal to the center of the crown base. As in other heterodontosaurids, the third premaxillary tooth is slightly larger than the first. In other ornithischians, premaxillary crowns tend to be subequal in size and have denticulate mesial and distal carinae (e.g., Lesothosaurus, Hypsilophodon; Naish and Martill 2001[19]; Sereno 1991[15]). Little else can be said about the premaxillary teeth given their state of preservation.

Galton (1978)[3] reconstructed the premaxillary tooth row with crowns of equal size (Fig. 19A), and Butler et al. (2012[20]; 6) reported that crown size does not increase posteriorly in the premaxillary series. The preserved portions of pm1 and 3 (Figs 11, 19B), however, clearly show an increase in size as occurs in most other heterodontosaurids.

Maxillary teeth

There are nine maxillary teeth (Figs 12–14), the first a nearly straight, transversely compressed caniniform tooth lacking any ornamentation on mesial or distal carinae (Fig. 11). Preserved only in the lectotypic left maxilla, the caniniform tooth has a relatively straight and slender crown that extends only a short distance below more distal maxillary crowns (Figs 12D, 13C, D). The maxillary caniniform tooth is preceded by an arched diastema for reception of the dentary caniniform tooth. The maxillary caniniform tooth is smaller than the dentary caniniform tooth (Fig. 19B), judging from the upper diastema and lack of an opposing lower diastema between the caniniform and third dentary tooth (Figs 15C, 16C). In Echinodon, thus, the upper caniniform tooth is positioned distal to a lower caniniform. In other heterodontosaurids, in contrast, the large third premaxillary crown is positioned mesial to a lower caniniform tooth (e.g., Lycorhinus, Heterodontosaurus).

Owen briefly described a second more mesial caniniform tooth in the maxilla based on a fragment and possible impression (Fig. 13C, D). Galton (1978)[3] regarded the fragment as a basal piece of the relatively complete caniniform tooth. Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: fig. 7A), however, added to the diagnosis the possibility of a second caniniform tooth based on Owen’s figures. Neither the tooth fragment nor the potential impression has survived. Available specimens, nonetheless, clearly indicate that only one caniniform is present at the anterior end of the maxilla. There is only a single empty alveolus for a caniniform tooth distal to the arched diastema in a right maxilla (Fig. 12), as correctly described by Galton (1978[3]: 143).

There are seven or eight postcaniniform teeth. Owen described the two lectotypic specimens that represent part and counterpart of a single specimen that was split from a single block of matrix. He indicated how the tooth rows on the opposing pieces should be aligned (Fig. 13). In the anterior piece (NHMUK 48209), there are two postcaniniform teeth; in the posterior piece (NHMUK 48210), there are five teeth plus one empty alveolus documenting the distal end of the tooth row. Owen correctly identified one of the teeth in the anterior piece as a replacement crown erupting beneath the anteriormost tooth in the posterior piece. Following this alignment, the total number of teeth in this complete maxillary series is eight (one caniniform tooth followed by seven postcaniniform teeth) (Fig. 19B). Based on the same specimens, Galton (1978)[3] suggested there are as many as 10 or 11 maxillary teeth, although his reasons for this higher number were not given. A second maxilla preserves the anteriormost alveolus for a caniniform tooth followed by six postcaniniform crowns (Fig. 12). A posterior piece with one and one-half crowns was originally present (Owen 1861[1]: pl. 8, fig. 3), suggesting that this individual had one additional postcaniniform tooth. On the basis of the available collection, thus, Echinodon has eight or nine teeth in the maxilla, including a mesial caniniform tooth followed by seven or eight teeth with denticulate crowns (Fig. 19B).

The first postcaniniform tooth (second maxillary tooth) has taller crown proportions than succeeding maxillary teeth; the crown is narrower and the denticulate portion of the crown is approximately 45% total crown height (Fig. 12C, D). Although the distalmost crown is not preserved, all of the remaining maxillary crowns are very similar in size and shape. In other heterodontosaurids, crown size is more variable and often substantially larger toward the middle of the maxillary series. Except for marginal ridges along mesial and distal crown edges, there are no ridges on either labial or lingual crown surfaces. There is a rounded median eminence, which is low on both sides but possibly slightly stronger on the lingual side (Figs 12, 14). There are approximately 8 to 10 denticles to each side of the apical denticle in most crowns. This denticle count is best observed in a nonfunctioning replacement crown in the second alveolus (NHMUK 48209). Galton (1978)[3] identified the median eminence as a “ridge” and suggested that there are fewer (only 5 or 6) denticles to each side of the crown apex.

The enamel is symmetrical on each side of the maxillary crowns as is visible in the cross-section of several crown tips. Wear facets are present on raised areas of the lingual face of the crowns of all fully erupted maxillary crowns that are well preserved and exposed in lingual view (Fig. 14B, C). These facets are more fully described below (see Discussion, Wear).

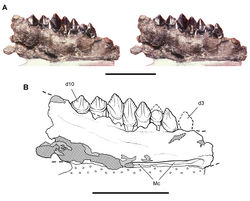

Dentary teeth

The dentary tooth row has 11 teeth, based on evidence from three dentaries with nearly complete alveolar margins (NHMUK 48214, 48215a, 48215b). The first dentary tooth must have had a very small peglike crown as in Lycorhinus, as the size of the alveolus is much smaller than any other in the dentary (Figs 15C, 16C). The root and base of the crown of this small tooth is preserved in one dentary (NHMUK 48214), and the small alveolus is preserved in the other two dentaries. The second dentary tooth, in contrast, is larger than all others, and judging from the elongate alveolus housed a caniniform tooth (Figs 15C, 16C). A substantial edentulous margin precedes both of these alveoli, a feature that distinguishes Echinodon from other heterodontosaurids and other basal ornithischians (Fig. 19B).

The small first dentary alveolus has never been described. Galton (1978[3]: Figs 1C’, F’, 2J) figured the large second alveolus and indicated the presence of a more mesial alveolus in one of the specimens (NHMUK 48215b). He did not comment on the size of these teeth and reconstructed the dentary tooth row without caniniform or peglike anterior teeth (Fig. 19A). The initial suggestion that Echinodon has a caniniform dentary tooth (Sereno 1997[18]) was criticized by Norman and Benton (2002[8]: 182) who stated “no known specimen displays evidence of either in situ caniniforms or natural moulds thereof”. Technically speaking, of course, the caniniform tooth itself is not preserved in any available specimens. Nonetheless, a caniniform tooth was surely present in Echinodon, given the size and shape of the alveolus in three available dentaries and the evidence of an opposing arched diastema in the maxilla. Like the caniniform teeth in other heterodontosaurids (e.g., Fruitadens; Butler et al. 2010[21]: fig. 3c, d), the alveolus and root are larger than adjacent crowns and angle ventrodistally rather than vertically. The enlarged alveolus in Echinodon, thus, should exhibit these features in a computed tomographic scan (Figs 15, 16).

There are eight and nine postcaniniform dentary teeth, respectively, in the left and right dentaries of NHMUK 48215. The left dentary, however, is incomplete posteriorly (Figs 15, 16) and appears to be missing the smaller distalmost tooth preserved on the right side. In the right series, dentary teeth 10 and 11 (postcaniniform teeth 8, 9) have progressively smaller crowns unlike the last two subequal alveoli on the left side. A total of 11 dentary teeth is also consistent with the teeth and alveoli in two other relatively complete dentaries (NHMUK 48213, 48214; Fig. 18). Galton’s (1978) estimate of 10 dentary teeth, therefore, is one too few (Fig. 19A), as he did not count the peg-shaped first dentary tooth.

The crowns of postcaniniform dentary teeth are well separated from their roots and have taller proportions than opposing maxillary crowns (Fig. 19B). All but the posterior three crowns are diamond-shaped, rather than subtriangular. The dorsal 50% of each of these crowns is denticulate, as opposed to approximately 25% in opposing maxillary crowns. Norman and Barrett (2002[8]: 177) stated that the denticles of both dentary and maxillary teeth are “confined to the apical one-third of the tooth crown”, but this is not true for crowns in the middle of the dentary series. As in postcaniniform maxillary crowns, postcaniniform dentary crowns typically have about 8 to 10 denticles to each side of the apical denticle. Likewise, only a median eminence is present on labial and lingual crown faces, and the roots are subconical and tapered where they are exposed (NHMUK 48215a).

The enamel is symmetrically distributed on each side of the dentary crowns as in maxillary crowns. Enamel also appears to cover a flattened subtriangular area on the mesial and distal sides of the crown base between the crown faces and root. This surface, which is present only on the largest crowns, was described previously as exposed dentine and highlighted as unique to Echinodon (Owen 1861[1]; Galton 1978[3]). I am unable to verify the absence of enamel or the fact that this surface is a unique, diagnostic feature of Echinodon.

Skull reconstruction

The reconstruction of the snout and dentition of Echinodon (Fig. 19B) is based on the original specimens and figures in Owen (1861)[1] and differs from a previous reconstruction (Figure 19A) in several regards. The premaxilla is shown with its alveolar margin offset ventral to the maxillary tooth row and with a significant edentulous border anterior to the first premaxillary tooth. The maxilla has a shorter series of postcaniniform teeth, above which is a significantly deeper buccal emargination. Dentary tooth 1 is rudimentary and followed by a large caniniform tooth, the tip of which inserts into an inset, arched diastema between the premaxilla and maxilla. The dentary also has a deeper buccal emargination, which dissipates anteriorly as it passes near the base of the caniniform tooth. Finally, the anterior end of the dentary, which articulates with a reconstructed predentary lacking processes, has an anterior dentary foramen with an incised vascular canal, above which is a significant edentulous margin. The new reconstruction removes any reasonable doubt about the heterodontosaurid status of Echinodon.

Taxon Treatment

- Sereno, P; 2012: Taxonomy, morphology, masticatory function and phylogeny of heterodontosaurid dinosaurs ZooKeys, 226: 1-225. doi

Images

|

Other References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 Owen R (1861) Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations. Part V. Lacertilia. Palaeontographical Society Monographs 12: 31-39.

- ↑ Owen R (1874) Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck formations. Supplement V. Dinosauria (Iguanodon). Palaeontographical Society Monographs 27: 1-18.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 3.19 3.20 3.21 3.22 3.23 3.24 3.25 3.26 3.27 3.28 Galton P (1978) Fabrosauridae, the basal family of ornithischian dinosaurs (Reptilia: Ornithopoda). Paläontologische Zeitschrift 52: 138-159.

- ↑ Galton P (1986) Herbivorous adaptations of Late Triassic and Early Jurassic dinosaurs. In: Padian K (Ed). The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs. Faunal Change Across the Triassic-Jurassic Boundary. Cambridge University Press, London and New York: 203-221.

- ↑ Benton M, Spencer P (1995) Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain. Chapman & Hall, London, 386 pp.doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-0519-4

- ↑ Galton P (2007) Teeth of ornithischian dinosaurs (mostly Ornithopoda) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of the western United States. In: Carpenter K (Ed). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington. Indiana University Press, Bloomington: 17-47.

- ↑ Norman D, Weishampel D (1985) Ornithopod feeding mechanisms: Their bearing on the evolution of herbivory. American Naturalist 126: 151-164. doi: 10.1086/284406

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 Norman D, Barrett P (2002) Ornithischian dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian) of England. In: Milner A Batten D (Eds). Life and Environments in Purbeck Times. Special Papers in Palaeontology 68. The Palaeontological Association, London: 161-189.

- ↑ Melville R, Freshney E (1982) The Hampshire Basin and Adjoining Areas. Her Majesty Stationery Office, London, 146 pp.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Salisbury S (2002) Crocodilians from the Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian) Purbeck Limestone Group of Dorset, southern England. In: Milner AR Batten D (Eds). Life and Environments in Purbeck Times. Special Papers in Palaeontology 68. The Palaeontological Association, London: 121-144.

- ↑ Clements R (1993) Type-section of the Purbeck Limestone Group, Durlston Bay, Swanage, Dorset. Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society 114: 181-206.

- ↑ Gradstein F, Ogg J (2009) The geologic time scale. In: Hedges S Kumar S (Eds). , The Timetree of Life. Oxford University Press, Oxford: 26-34.

- ↑ Lydekker R (1888) Catalogue of the Fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural History) Part I. British Museum of Natural History, London, 309 pp.

- ↑ Beckles S (1854) On the Ornithoidichnites of the Wealden. Quarterly Journal of the GeologicalSociety, London 8: 456-464. doi: 10.1144/GSL.JGS.1854.010.01-02.52

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 Sereno P (1991) Lesothosaurus, “fabrosaurids,” and the early evolution of Ornithischia. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11: 168–197. doi 10.1080/02724634.1991.10011386

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Galton P (1974a) The ornithischian dinosaur Hypsilophodon from the Wealden of the Isle of Wight. Bulletin, British Museum (Natural History) Geology 25: 1-152.

- ↑ Gow C (1990) A tooth-bearing maxilla referable to Lycorhinus angustidens Haughton, 1924 (Dinosauria, Ornithischia). Annals of the South African Museum 99: 367-380.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Sereno P (1997) The origin and evolution of dinosaurs. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 25: 435-489. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.25.1.435

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Naish D, Martill D (2001) Ornithopod dinosaurs. In: Martill D Maish D (Eds). , Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association, Dorchester: 60-132.

- ↑ Butler R, Porro L, Galton P, Chiappe L (2012) Anatomy and cranial functional morphology of the small-bodied dinosaur Fruitadens haagarorum from the Upper Jurassic of the USA. PLoS One 7: e31556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031556.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Butler R, Galton P, Porro L, Chiappe L, Henderson DM et a (2010) Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277: 375-381. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1494

- ↑ Broom R (1911) On the dinosaurs of the Stormberg, South Africa. Annals of the South African Museum 7: 291-307.

- ↑ Zheng X, You H, Xu X, Dong Z (2009) Early Cretaceous heterodontosaurid dinosaur with integumentary structures. Nature 458: 333–336. doi: 10.1038/nature07856

![Figure 2. Early heterodontosaurid discoveries. A Lithographic drawing of the right and left premaxillae and the anterior portion of the left maxilla in lateral view of Echinodon becklesii (NHMUK 48209; from Owen 1861[1]) B Drawing of lower jaws in dorsal view of Geranosaurus atavus (SAM-PK-K1871; from Broom 1911[22]) C Photograph of the posterior portion of a subadult skull in right lateral view of Heterodontosaurus tucki (AMNH 24000). Scale bars equal 1 cm in A and 2 cm in B and C.](https://species-id.net/o/thumb.php?f=ZooKeys-226-001-g002.jpg&width=175)

![Figure 9. More recent heterodontosaurid discoveries from northern locales. A Jaws of Fruitadens haagarorum from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation in Colorado, USA (based on LACM 115747, 128258; reversed from Butler et al. 2010[21]) B Left dentary in lateral view of an undescribed heterodontosaurid from the Lower Jurassic Kayenta Formation of Arizona (from Sereno et al. unpublished) C Partial skull of Tianyulong confuciusi from the Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, PRC (STMN 26-3; reversed from Zheng et al. 2009[23]). Abbreviations: a angular ad 9, 10 alveolus for dentary tooth 9, 10 adf anterior dentary foramen antfo antorbital fossa apd articular surface for the predentary d dentary d1, 2, 8 dentary tooth 1, 2, 8 emf external mandibular fenestra en external nares j jugal l lacrimal m maxilla n nasal pd predentary pf prefrontal pm premaxilla po postorbital q quadrate qj quadratojugal sa surangular. Scale bar equals 1 cm in A and C and 5 mm in B.](https://species-id.net/o/thumb.php?f=ZooKeys-226-001-g009.jpg&width=201)

![Figure 12. Maxilla of Echinodon becklesii from the Lower Cretaceous Purbeck Formation of England. Right maxilla in lateral view (NHMUK 48211). Lithograph (A) and line drawing (B) from Owen (1861)[1]. Stereopair (C) and line drawing (D). Hatching indicates broken bone; dashed lines indicate estimated edges. Scale bars equal 5 mm. Abbreviations: adi arched diastema am articular surface for the maxilla antfe antorbital fenestra be buccal emargination fo foramen j jugal m1, 2, 7 maxillary tooth 1, 2, 7 pl palatine ppf postpalatine foramen rm rim.](https://species-id.net/o/thumb.php?f=ZooKeys-226-001-g012.jpg&width=220)

![Figure 13. Maxilla of Echinodon becklesii from the Lower Cretaceous Purbeck Formation of England. Part (NHMUK 48210) and counterpart (NHMUK 48209) of a block preserving portions of the snout of a skull. A, B Part preserving the posterior portion of the left maxilla and portions of the left lacrimal, jugal and ectopterygoid in medial view (NHMUK 48210; reversed from Owen 1861[1]). C, D Counterpart preserving portions of the right and left premaxillae and the anterior portion of the left maxilla in lateral view (NHMUK 48209; from Owen 1861[1]). A red asterisk marks a crown on the part (A) and its impression on the counterpart (C). Abbreviations: idt impressions of dentary teeth imt impressions of maxillary teeth l left m maxilla pm premaxilla.](https://species-id.net/o/thumb.php?f=ZooKeys-226-001-g013.jpg&width=194)

![Figure 19. Skull of Echinodon becklesii from the Lower Cretaceous Purbeck Formation of England. Skull reconstructions in left lateral view. A From Galton (1978)[3]. B This study. Dashed lines indicate estimated edges and sutures. Abbreviations: adf anterior dentary foramen adi arched diastema apmf anterior premaxillary foramen be buccal emargination cp coronoid process d dentary d1, 2, 11 dentary tooth 1, 2, 11 fo foramen j jugal l lacrimal m maxilla m1, 2, 8 maxillary tooth 1, 2, 8 pd predentary pm premaxilla pm1, 3 premaxillary tooth 1, 3.](https://species-id.net/o/thumb.php?f=ZooKeys-226-001-g019.jpg&width=213)